Author: Isabel Cooper-Oakley

This is a most complete and excellent telling of the life of Count Saint Germain. Many private letters and documents are quoted to talk about the Count from the perpective of others who knew and interacted with him.

These quotes serve to solidify his existence as a real person in Europe’s history while still showing his mysteriuos persona through the eyes of other people from the aristocracies who existed at the time that he was alive.

I really enjoyed this book. It is fascinating how the man became a myth that I want to believe in. This book has all the compelling detail you’ve ever heard about Count of St. Germain and more.

Review: The Comte de St. Germain: The Secret of Kings

By Isabel Cooper-Oakley (Milan: G. Sulli-Rao, 1912)

Isabel Cooper-Oakley’s The Comte de St. Germain: The Secret of Kings is a work perched between biography, legend, and devotional literature. Published in 1912, at the height of the Theosophical revival, it presents not so much a conventional historical study as a spiritual portrait of one of Europe’s most enigmatic figures. Cooper-Oakley, already known within Theosophical circles as a translator and essayist on occult traditions, undertakes here to stitch together scattered archival traces, memoir fragments, and rumor into a coherent narrative that portrays St. Germain not as charlatan but as adept, philosopher, and emissary of a higher brotherhood.

The book is framed from its opening pages by a distinctly Theosophical sensibility. Quoting H. P. Blavatsky on the cyclic appearance of adepts at the close of each century, Cooper-Oakley positions St. Germain as precisely such a figure, an Oriental initiate who brought wisdom and warning to the courts of Europe. This sets the interpretive ground: the Count is read less as a man of ambiguous biography and more as a spiritual archetype, an agent of what Blavatsky would call the Great Lodge. Yet Cooper-Oakley is not wholly uncritical; she acknowledges the swirl of rumors—charges of adventurism, questions about finances, even doubts about identity—but she subsumes them into a narrative of misunderstood genius.

Structurally, the book is both ambitious and uneven. Its eight main chapters proceed thematically: from St. Germain as mystic and philosopher; to his astonishing range of travels across Venice, Persia, London, Vienna, India, Paris, and St. Petersburg; to his prophetic warnings to Marie Antoinette and Louis XVI; to his political missions for Louis XV; and finally to his ties with Freemasonry, Mesmer, and the Austrian occult underground. Seven appendices collect supporting archival material: correspondence between Choiseul and Affry, extracts from the Mitchell Papers, Dutch memoirs, French Masonic documents, and records concerning his supposed death. The effect is of a dossier—a cabinet of curiosities—gathered to shore up a figure who resists containment.

Cooper-Oakley’s greatest strength lies in her ability to evoke atmosphere. We see the Count at Chambord, conducting alchemical experiments in a laboratory granted by Louis XV; we overhear him at Versailles, dazzling with music and jewels, but counseling restraint, prophecy, and moral reform; we follow him to Brussels and Leghorn, to Triesdorf and Leipzig, where his assumed names—Bellamarre, Tzarogy, Ragoczy—cloak him in a haze of romance. Anecdotes are marshaled with dramatic flair: Madame d’Adhémar’s recollections of St. Germain appearing decades after his recorded death; Casanova’s bemused encounter with him in Armenian disguise; Horace Walpole’s letters describing him as a “mad” musician in London. Each vignette reinforces the sense of a man both everywhere and nowhere, shimmering across Europe’s eighteenth-century salons like a ghost with a violin.

At the same time, the book cannot escape its limitations. Cooper-Oakley writes with fervor but not with critical detachment. Her citations are uneven, often anecdotal, and her interpretive lens is unmistakably Theosophical. Where a historian might weigh probabilities or parse contradictions, she embraces mystery as evidence of higher calling. Thus the countless aliases are read not as signs of a political operative or adventurer but as veils required by his mission. His unexplained wealth is not interrogated through mundane economics but attributed to noble lineage and the Medici’s patronage. Even the question of his death—recorded in 1784 yet belied by later sightings—is left open, a miracle rather than a problem.

And yet, to fault Cooper-Oakley for these tendencies is to miss the book’s peculiar achievement. It is less a biography than a mythography, a record of how St. Germain was remembered, refracted, and exalted across centuries. In this sense, the contradictions are not weaknesses but part of the story itself: he is precisely the figure who cannot be pinned down, who dissolves in the historian’s grasp, only to reappear decades later in another court, another disguise, another prophecy. By weaving together gossip, state archives, memoirs, and occult speculation, Cooper-Oakley produces a portrait that is as elusive as her subject, but also as haunting.

The literary quality of the book, while not without florid excess, captures something essential. Cooper-Oakley writes with reverence, but also with a kind of romantic melancholy, aware that her sources are fragmentary, that the man remains just beyond reach. This, paradoxically, is what gives the work its enduring charm. St. Germain emerges less as a man of flesh and blood than as a symbol of Europe’s fascination with secrecy, immortality, and hidden wisdom—a mirror in which mystics, monarchs, and modern readers alike glimpse their own longings for transcendence.

In the end, The Comte de St. Germain: The Secret of Kings must be read as both history and myth, scholarship and hagiography. It is not definitive in any empirical sense, but it remains one of the most influential modern attempts to capture the aura of a man Voltaire once described as “a man who never dies.” For students of mysticism, alchemy, and the esoteric imagination, it is a work that, despite its biases, illuminates both its subject and the Theosophical milieu that sought to claim him.

Perhaps it’s best to approach Cooper-Oakley’s book as a myth-biography—valued not for factual certainty but for its ability to distill the legend of St. Germain into a compelling narrative, one that reveals as much about the twentieth-century hunger for hidden masters as it does about the enigmatic Count himself. But I will leave it up to you to decide.

Here is an excerpt from the book:

“The original ‘International Man of Mystery,’ the Count St. Germain, was an 18th century European aristocrat of unknown origin. He had no visible means of support, but no lack of resources, and moved in high social circles. He was a renowned conversationalist and a skilled musician. He dropped hints that he was centuries old and could grow diamonds. He never ate in public, was ambidextrous, and as far as anyone could tell, totally celibate. He served as a backchannel diplomat between England and France, and may have played some role in Freemasonry. He hobnobbed with Marie Antoinette, Catherine the Great, Voltaire, Rousseau, Mesmer, and Casanova. He dabbled in materials and textile technology as well as alchemy, as did many intellectuals of the time (e.g., Newton). These are established historical facts, documented by the extensive collection of contemporary accounts in this book.

Less well understood are some of the other stories that have been made about the elusive Count: he always appeared about forty years old, popped up from time to time after his official death (on February 27th, 1784), made spot-on, unambiguous prophecies, could transmute matter, and spontaneously teleported to distant locations. This has made him a subject of interest for students of the esoteric. The Theosophists, (of which Ms. Cooper-Oakley was a founding member), considered St. Germain to be one of the hidden immortals who manipulate history. In the 20th century, the “I Am” Activity, and its successors such as Elizabeth Clare Prophet’s adherents, elevated St. Germain to the status of a demigod, an ‘Ascended Master.’

There is probably a good explanation for some of the anomalies in the narrative. Many of the memoirs of St. Germain were written years after the events, and undoubtedly embellished in the telling.”

Read it from photographs of a copy of the book here.

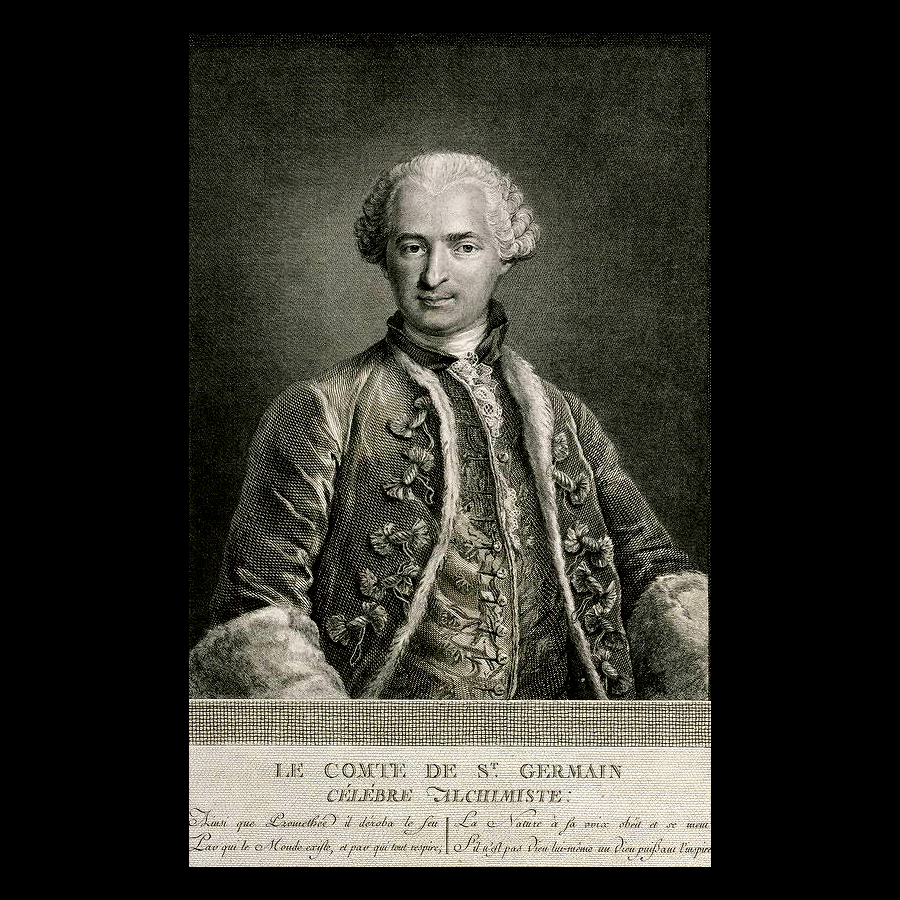

Count of St. Germain

A common representation of St. Germain