Count Saint-Germain: Facts, Legends, and the Surviving Works

Origins and Early Life

Historical records of the Comte de Saint-Germain begin in the 1740s, yet his origins remain uncertain.

Most credible evidence links him to Prince Francis II Rákóczi of Transylvania, exiled after 1711, which would make Saint-Germain the prince’s illegitimate son. This hypothesis, first outlined in Isabel Cooper-Oakley’s The Comte de St. Germain (1912) and later referenced in Deschamps, Histoire de la Franc-maçonnerie (1861), aligns with reports of noble education and multilingual mastery.

Documents show his early years spent between Vienna, Venice, and Pisa, educated by the Medici and other Italian patrons. He spoke fluent French, German, Italian, Spanish, and English; played the violin professionally; and wrote chemical and philosophical treatises.

Presence in European Courts

Saint-Germain appeared in London (1745), suspected of espionage yet never charged. By the 1750s, he was in Paris, working under Louis XV and Madame de Pompadour.

He presented dyes, cosmetics, and jewels, claiming secret methods for purifying metals and prolonging life.

The French court archives (Correspondance Politique de France, vol. 437) record his diplomatic missions and note that he “never ate in public, never aged, and seemed tireless.”

He continued corresponding with Voltaire, who in 1761 quipped:

“A man who knows everything and never dies.”

While satirical, the comment crystallized the Count’s enduring legend.

The Rosicrucian and Masonic Connection

Evidence of Saint-Germain’s involvement in esoteric societies appears in scattered 18th-century archives:

-

The Avignon Society records of Antoine-Joseph Pernety list him among correspondents in 1760–1770.

-

A photograph published in Rosicrucian Digest (1933) allegedly shows him among initiates of a later Rosicrucian revival, though authenticity remains unverified.

-

His philosophy closely mirrors Rosicrucian ideals of inner alchemy—self-perfection rather than transmutation of metals.

Later Theosophists (notably Édouard Schuré and Franz Hartmann) recast him as an “adept” who inspired mystical movements from Paris to Leipzig, though these sources blur fact and myth.

The Surviving Manuscripts

Several manuscripts are attributed to him or his circle:

-

The Most Holy Trinosophia (1790 MS, Library of Troyes / Phoenix Press 1933 ed.) — a visionary initiation text blending Hermetic, Egyptian, and Kabbalistic imagery.

-

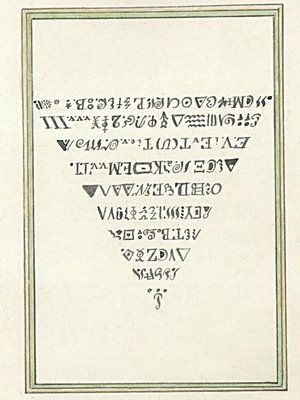

The Triangular Book of Saint-Germain (MS 209, Getty Research Institute) — a ciphered ritual promising discovery of treasures and long life, analyzed in Three Hands of the Triangular Book and The Ritual Explained (Philosopher’s Stone Online).

-

Other minor fragments referenced in Hall’s Secret Teachings of All Ages and in Des Erreurs et de la Vérité (1775), likely later copies.

Together they suggest a coherent cosmology: geometric ritual, purification, and illumination—concepts paralleling early Rosicrucian Hermeticism.

Saint-Germain as Musician

Contemporary accounts confirm Saint-Germain’s talent as a composer and violinist.

The British Library Add. MS 23560 lists Six Sonates pour violon et basse continue (1745); further authenticated works include Six Trios (Paris, 1749) and Airs and Songs (1751) preserved at UCL Library.

In 2010, musicologist Ioannis Chrissochoidis prepared The Music of the Count of St. Germain: An Edition (UCL Discovery), assembling forty authenticated works—arias, solos, trio sonatas, and English songs—drawn from archives in London and Vienna. The manuscripts survive in scattered European collections but remain largely unrecorded.

A documented 2012 UCL recital featured Violin Sonata No. 3 in D major, offering a rare glimpse into Saint-Germain’s musical voice—refined, lyrical, and stylistically aligned with the cosmopolitan elegance of mid-18th-century chamber music.

Final Years and Afterlife of the Legend

Saint-Germain was last seen at the court of Prince Karl of Hesse-Kassel (c. 1784 – 1788), experimenting with dyes and medicinal preparations. A record in the Schleswig archives notes his death in 1784—but later letters and Masonic minutes mention him alive in 1790 and 1801.

These reports fueled the belief in his immortality—an idea that Theosophy and Rosicrucianism adopted enthusiastically.

The Count’s myth merged with Hermetic archetypes: the wandering adept, the immortal teacher, the guardian of lost science. Texts bearing his name—Trinosophia, Triangular Book, and alchemical letters—reflect a consistent theme: that enlightenment is a science of transformation rather than mere metallurgy.

Legacy and Continuing Research

Today, Saint-Germain’s verified music and ritual texts offer rare points of contact between European esotericism and historical record. Manly P. Hall called him “a prototype of the philosophic adept who turns legend into living symbol.”

Whether chemist, diplomat, or mythmaker, his life bridged two worlds—the rational Age of Reason and the mystical current of Hermetic humanism.

Further authenticated materials are available through the Getty Research Institute (MS 209 facsimile) and the UCL Music Repository (Chrissochoidis Edition). Ongoing digital initiatives seek to record his complete works for public release.

🜍 Further Reading

Saint Germain’s Triangular Book: The Ritual Explained

Learn how geometry, invocation, and the “Levite” assistant form the core of the Count’s ceremonial method.

The Triangular Book of Saint Germain: Complete Translation and Comparative Notes

Full translation of the ritual from MS 209 / 210 / Wellcome 4668 with annotated textual variants.

The Divine Names of the Triangular Book

Examines the Hebrew-Greek composite “barbarous names” and their link to classical grimoires.

The Saint-Germain Circle: Hermetic Networks of the Eighteenth Century

Profiles the noble and esoteric figures surrounding the Count in Paris, Venice, and Vienna.

The Ritual Exemplar of MS 209

Overview of the Manly P. Hall facsimile—its diagrams, provenance, and preservation at the Getty Research Institute.