Philosopher’s Stone Part Six:

Testamentum of Pseudo-Llull — The Philosophers’ Water and Middle Nature

Testamentum of Pseudo-Llull — The Philosophers’ Water and Middle Nature

Bibliographic Introduction

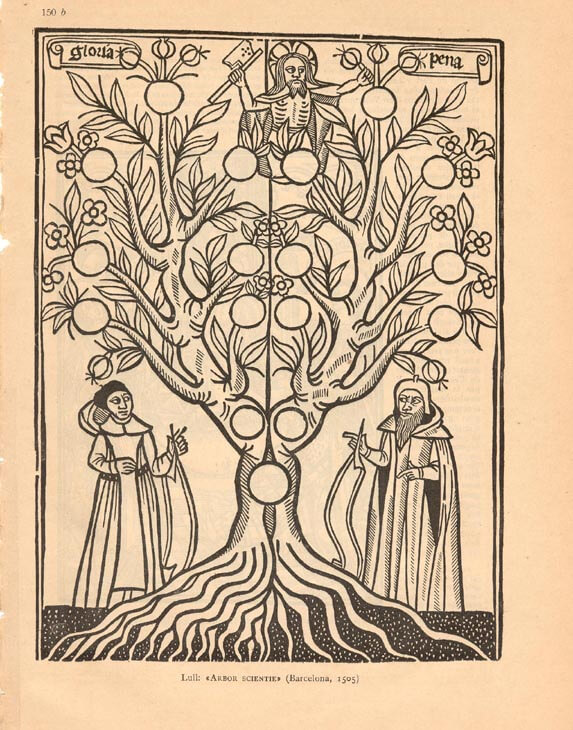

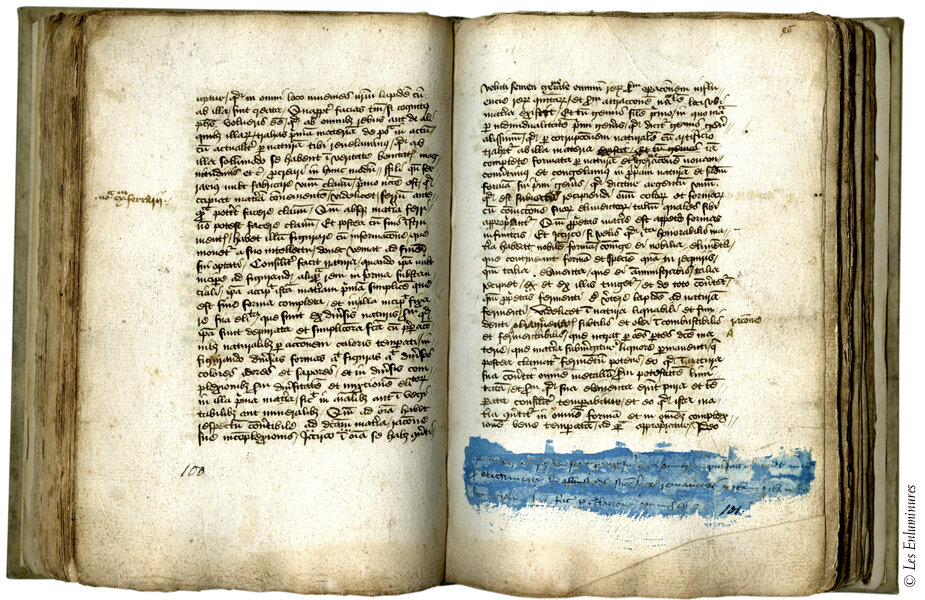

The Testamentum attributed to Ramon Llull (1232–1316) is not an authentic work of the Majorcan philosopher but a 14th-century pseudoepigraphic text. While Llull himself wrote on theology, logic, and missionary philosophy, later alchemical writers borrowed his name to lend authority to their works. Among these, the Testamentum became one of the most influential, circulating widely in manuscript and later print, shaping the European understanding of the philosophers’ stone.

The treatise presents a systematic exposition of alchemy, emphasizing unity of subject, the primacy of philosophical water, the mediating “middle nature,” and the transformation of metals through a sequence of color changes.

Philosophical Mercury in the Testamentum

At the core of the Testamentum lies the doctrine of philosophical water, described as a metallic phlegm or humidity. The text declares:

“Our Secret Philosophical Water is compounded of three Natures, and it is like to a Mineral Water, in which our Stone is dissolved, and therein it is terminated, Whitened and rubified.”

This water is called the first water of mercury:

“It is the middle substance, and the first Water of Mercury, in which the beginning of the Stone is, that is, its dissolution.”

The author insists that this is not common quicksilver, but a moist, phlegmatic principle hidden in metals, capable of dissolving and nourishing. It is the middle nature, uniting opposites:

“This is called the middle nature, and the Stone, Mercury, Arsenick, and the noble spirit partaking of both extremes, the White Sulphur and the Red.”

Philosophical mercury is therefore defined as a spiritual water within metallic bodies, mediating between volatile and fixed, white and red, body and spirit.

Extracting the Method

The Testamentum outlines the following operations:

-

Dissolution in Philosophical Water: The Stone is dissolved in the secret water, which prevents combustion and initiates putrefaction.

-

Separation of Phlegm: Decoction separates the phlegm, carrying the spirit, which allows repeated imbibition.

-

Color Sequence: The matter turns black (corruption), pale like wheat chaff, then white as the spirit is released, and finally red through continued decoction.

-

Fixation: The volatile is fixed and spirit conjoined to body, producing a substance partly fixed, partly volatile.

-

Union of Sol and Argent Vive: Gold and argent vive (not vulgar quicksilver, but the hidden humidity) are united by the middle nature, yielding tincting sulfur.

-

Fermentation: The ferment strengthens the compound, producing a red powder that tinges silver into gold.

This procedure is entirely consistent with prior tradition: one vessel, one water, continuous fire, with transformation marked by stages of color.

Evidence of Practice

The Testamentum includes operational details—sublimation, decoction, filtration, the use of porphyry stones and alembics—that suggest acquaintance with laboratory practice. While couched in allegory, the technical references go beyond mere bookish speculation. The repeated emphasis on phlegm, prevention of combustion, and regulation of fire implies some experimental familiarity.

Even so, the treatise is more scholastic synthesis than the notes of a single adept. Its language fuses practical imagery with philosophical argumentation.

Contribution to the Stone Tradition

The Testamentum makes three enduring contributions to alchemy:

-

Middle Nature Doctrine: Philosophical mercury is explicitly a middle substance uniting extremes of volatile and fixed, white and red.

-

Philosophical Water: It defines the “first water of mercury” as the indispensable agent of dissolution and transformation.

-

Refined Color Sequence: Black → pale chaff → white → red. This nuanced sequence influenced many later adepts.

After Arnaldus de Villanova had warned against mistaking common quicksilver for the philosophers’ mercury, the Testamentum reasserts what mercury truly is: a metallic humidity, mediating opposites, and nourishing transformation.

Deciphered Method

Distilled to essentials, the Testamentum teaches:

-

Extract the philosophical water, the first water of mercury, from metallic bodies.

-

Dissolve the Stone in this water; allow black putrefaction.

-

Through decoction, separate the phlegm, producing paleness.

-

Continue heating to whiteness, then redness.

-

Unite Sol and argent vive through the middle nature; fix the volatile in body.

-

Ferment and project: a red powder tincts silver into gold.

Here, philosophical mercury is clearly the secret metallic water, the middle nature between extremes.

Conclusion

The Testamentum attributed to Ramon Llull is one of the most influential medieval expositions of the philosophers’ stone. Though spurious, it deeply shaped European alchemical thought, defining philosophical mercury as a secret metallic water and elaborating the doctrine of the middle nature.

Its clarity—dissolution, phlegm separation, color changes, fixation, fermentation—gave adepts a practical-seeming framework, echoed by Ripley and Philalethes centuries later. The text reinforces a central truth of the alchemical tradition: the philosophers’ mercury is not vulgar quicksilver, but an inner metallic principle, volatile and fixed together, mediating transformation.

| Author / Text | Philosophical Mercury | Preparation Steps | Union Method | Fire / Heat | Color Signs | Product Claims |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Zosimos of Panopolis (c. 300 CE) | “Divine water” in the kerotakis; volatile spirit ascending and descending | Calcination, sublimation, distillation, washing | Circulation in sealed vessel; dissolution and recombination | Gentle, regulated heating; moist fire | Blackening, whitening, reddening | Tincture, purification of metals; spiritual rebirth |

| Emerald Tablet (Arabic/Latin, 9th–12th c.) | “One Thing” mediating heaven and earth; volatile principle implied | None explicit; “separate the subtle from the gross” | Circulation: ascent and descent of the subtle | Not named; implied gentle force | None specified; allegorical “glory of the whole” | Perfection of all things; universal power |

| Turba Philosophorum (12th c., Arabic → Latin) | Permanent water: vinegar/gum/spume of Luna; volatile-fixative solvent | Putrefaction 40 days; washing; imbibition; coagulation | Copper (sometimes with lead/tin) dissolved in permanent water | Gentle fire; sealed vessel; staged regimen | Blackening → Whitening → Reddening → Tyrian purple | Tincture of metals; Stone “not a stone”; invariable color |

| Artephius, Secret Book (12th c.) | Hidden mercury within antimony; combined with gold | Dissolution of Sol/Luna in “living water” (moist fire); putrefaction | Antimony + mercury + gold in one vessel | Gentle, continuous heat (“hen brooding eggs”) | Black → White → Red | Incombustible oil; multiplicative tincture; longevity |

| Pseudo-Geber, Summa Perfectionis (13th c.) | Purified, sublimed, partly fixed quicksilver | Repeated sublimation with salts/vitriols; fixation of volatile | Mercury + purified sulfur joined in vessel | “Convenient fire”: moderate, continuous decoction | Black → White → Red | Philosophers’ Stone (Elixir); projection of metals; medicinal virtues |

| Arnaldus de Villanova, Epistle (late 13th–early 14th c.) | Hidden mercurial humidity within metallic bodies; not common quicksilver | Dissolution, putrefaction | Unite body and hidden mercury in vessel | Gentle, continuous fire | Black → White → Red | Incombustible Stone; tincture of metals |

| Pseudo-Llull, Testamentum (14th c.) | Philosophical water: metallic phlegm; first water of mercury; middle nature uniting extremes | Dissolution in water; decoction; separation of phlegm; imbibition | Union of Sol and argent vive via middle nature | Continuous gentle fire; decoction, filtration | Black → Pale chaff → White → Red | Red powder tincts silver into gold; Stone of projection |