Philosopher’s Stone Part One: The Emerald Tablet and Zosimos of Panopolis — First Clues to the Stone

Philosopher’s Stone Part One: The Emerald Tablet and Zosimos of Panopolis — First Clues to the Stone

Bibliographic Introduction

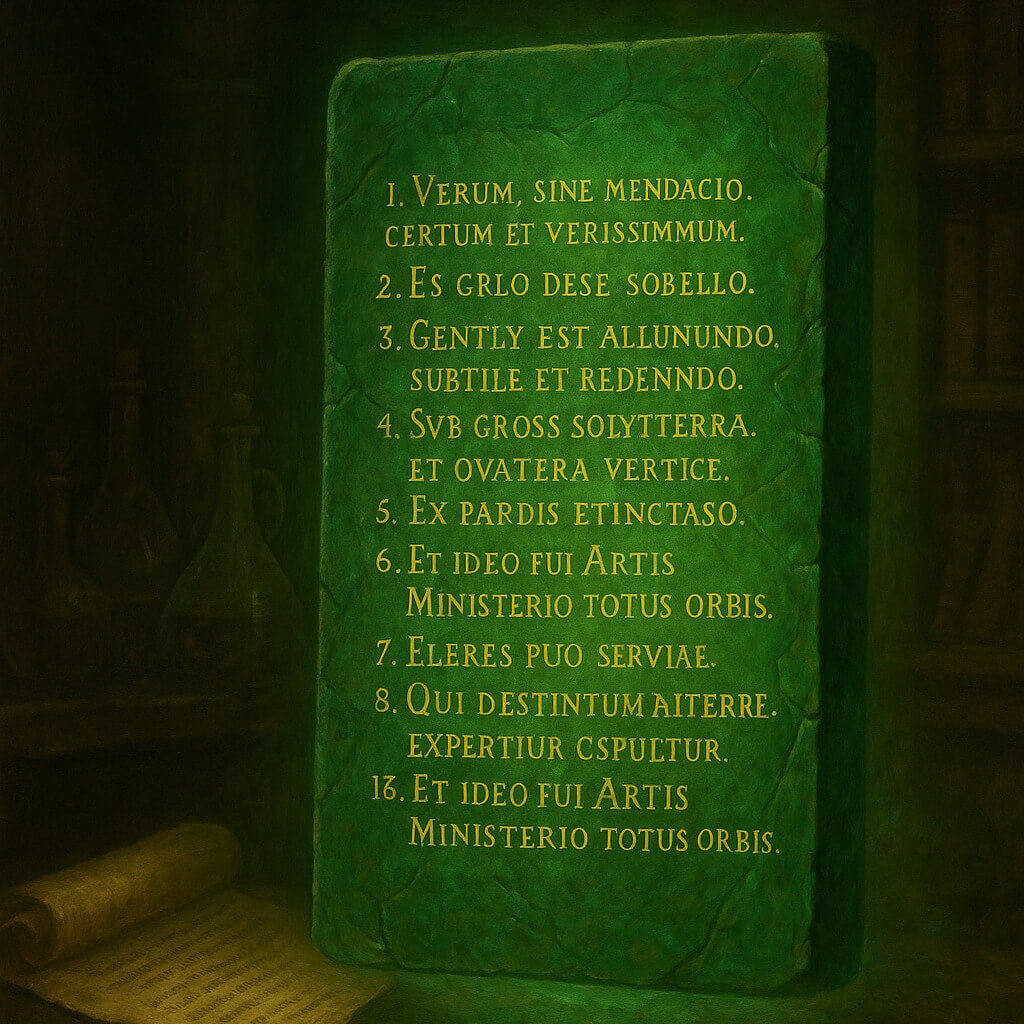

Two voices stand at the threshold of Western alchemy. The first is the Emerald Tablet (Tabula Smaragdina), a short collection of aphorisms attributed to Hermes Trismegistus. Its earliest witnesses appear in Arabic Hermetica of the ninth and tenth centuries, later rendered into Latin by translators such as Hugo of Santalla in the twelfth century. The text is no more than a page long, but its lines have echoed for centuries: “That which is above is like that which is below.”

The second is Zosimos of Panopolis, an Egyptian-Greek alchemist writing around 300 CE in Panopolis (modern Akhmim). Portions of his works survive in Byzantine compilations and fragments of his Authentic Memoirs. Zosimos is the first historical figure whose writings combine both visionary allegory and laboratory description.

Neither the Tablet nor Zosimos describe the philosophers’ stone in its later medieval form, but both provide the groundwork. The Tablet establishes the symbolic logic of a “One Thing” mediating heaven and earth. Zosimos shows, for the first time, actual operations of dissolution, sublimation, and recombination. Together, they provide the conceptual charter and the laboratory sketch for what will later become the magistery of the Stone.

Philosophical Mercury in the Emerald Tablet

The Tablet never names mercury, nor sulfur, nor salt. Yet it describes a process:

“It ascends from the earth to heaven and again descends to the earth, and receives the power of the higher and the lower.”

This is circulation—the subtle rising, the gross descending, the reunion of opposites. The “One Thing” of the Tablet is less a chemical than a cosmological principle, yet later authors will interpret it as the prima materia, the philosophical mercury.

What can be said here? The Tablet implies that the true subject is a mediating spirit capable of rising and descending, separating and uniting. That is precisely how later adepts describe philosophical mercury: subtle, volatile, able to ascend as vapor and descend as tincture, uniting heaven and earth in the vessel. In this sense, the Tablet anticipates mercury not by name but by function.

Philosophical Mercury in Zosimos

Zosimos brings us into the workshop. He describes apparatus—the kerotakis, a sealed vessel in which vapors rise, condense, and descend back into the matter. He speaks of “divine water” that dissolves metals, of whitening and reddening, of vapors that suffocate the unwary operator.

He does not call this water “philosophical mercury,” but the parallels are clear. The divine water is volatile yet penetrating; it ascends and descends within the vessel; it dissolves metals and brings them to rebirth. This is the very role mercury will play in later treatises. In Zosimos we encounter it not as a doctrine but as a fluid in the vessel, at once real solvent and spiritual symbol.

Method Clues from the Emerald Tablet

The Tablet offers no recipe, but it encodes a structure of operation:

-

Subject: a “One Thing” in which heaven and earth meet.

-

Operation: separation of subtle from gross, ascent and descent.

-

Fire: not named, but implied as the gentle force that drives circulation.

-

Signs: glory, perfection, the “force strong with all force.”

In practical terms, this reads like a riddle of distillation: vapor rising, condensing, and rejoining the body until a new unity is achieved. Philosophical mercury, though unnamed, is foreshadowed as the agent of circulation.

Method Clues from Zosimos

Zosimos is more explicit. He describes:

-

Apparatus: the kerotakis, a sealed system for heating and condensation.

-

Matter: copper compounds, sulfur, mercury, vitriols—substances available in his time.

-

Operations: calcination, distillation, sublimation, washing, coction (gentle digestion).

-

Signs: blackening (death), whitening, reddening (rebirth).

-

Philosophical principle: a divine water, volatile yet transformative, capable of dissolving bodies and giving them new form.

What Zosimos contributes is the first credible account of a method: seal a matter in a vessel, heat it gently, let its subtle part rise and descend until the body is transformed. The “philosophical mercury” here is not a doctrine but an observed process: the volatile spirit that ascends and descends in the kerotakis.

Assessment: Practitioner or Compiler?

The Tablet is a compilation, a symbolic creed. Its value lies in authority, not practice. It names no vessels, no hazards, no failures.

Zosimos, by contrast, is unmistakably a practitioner. He knew the smell of fumes, the hazard of suffocation, the behavior of substances under heat. His allegories are visionary, but they are welded to real observations. He is the first witness we can trust to have actually tended a fire and watched vapors condense against glass.

Contribution to the Stone Tradition

What do these two sources give us in the search for the philosophers’ stone?

-

The Tablet gives us the idea of a mediating “One Thing,” ascending and descending. Later writers will identify this with philosophical mercury.

-

Zosimos gives us the prototype of the method: a sealed vessel, gentle fire, circulation of vapors, color changes as signs. Later writers will perfect this into the regimen of the Stone.

Together, they establish the grammar: one vessel, continuous fire, circulation, and color stages. The precise identity of philosophical mercury is not yet fixed, but its profile—volatile, transformative, mediating—has already emerged.

Conclusion

The Emerald Tablet and Zosimos of Panopolis are not manuals for making the Stone, but they are the foundation. The Tablet declares that there is one subject through which heaven and earth are reconciled. Zosimos shows what this looks like in practice: vapors rising and descending in a sealed vessel, a divine water dissolving bodies and remaking them, colors unfolding as proof of progress.

From these beginnings, the tradition of philosophical mercury is born. It is the volatile spirit that circulates, dissolves, unites. It will be named, redefined, and disputed in centuries to come, but its outline is already visible here. The Tablet gave the principle; Zosimos gave the operation. Together, they mark the true beginning of the quest for the philosophers’ stone.

| Author / Text | Philosophical Mercury | Preparation Steps | Union Method | Fire / Heat | Color Signs | Product Claims |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Emerald Tablet (Arabic/Latin, 9th–12th c.) | “One Thing” mediating heaven and earth; volatile principle implied | None explicit; “separate the subtle from the gross” | Circulation: ascent and descent of the subtle | Not named; implied gentle force | None specified; allegorical “glory of the whole” | Perfection of all things; universal power |

| Zosimos of Panopolis (c. 300 CE) | “Divine water” in the kerotakis; volatile spirit ascending and descending | Calcination, sublimation, distillation, washing | Circulation in sealed vessel; dissolution and recombination | Gentle, regulated heating; moist fire | Blackening, whitening, reddening | Tincture, purification of metals; spiritual rebirth |