Three Hands of the Triangular Book: The Living Cipher of Saint-Germain

1. Three Triangles on One Table

Imagine three manuscripts resting on a wooden desk in uneven light.

All bear the same name: Le Livre Triangulaire du Comte de Saint-Germain.

Yet none is quite the same book.

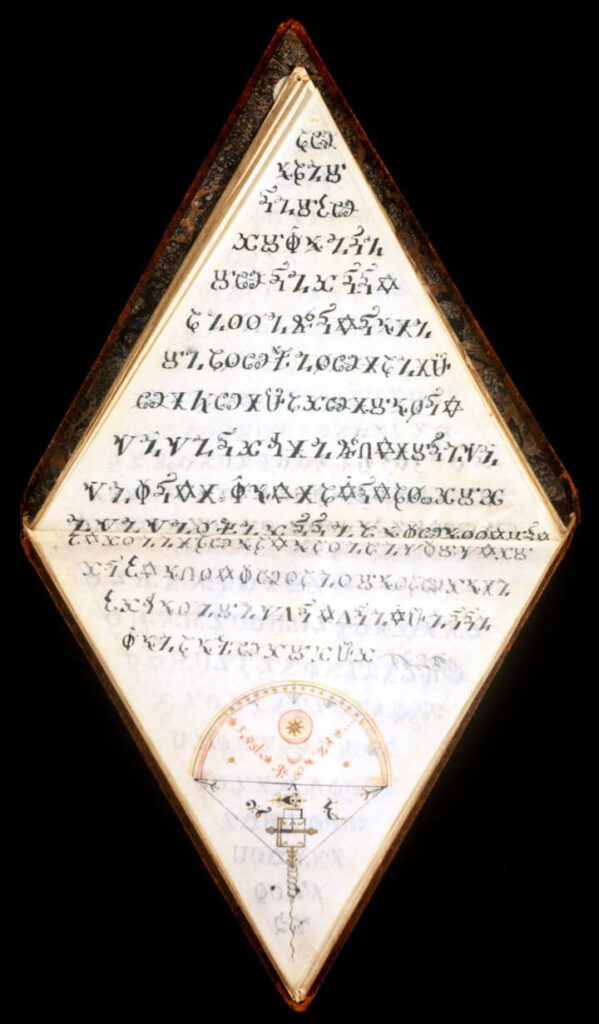

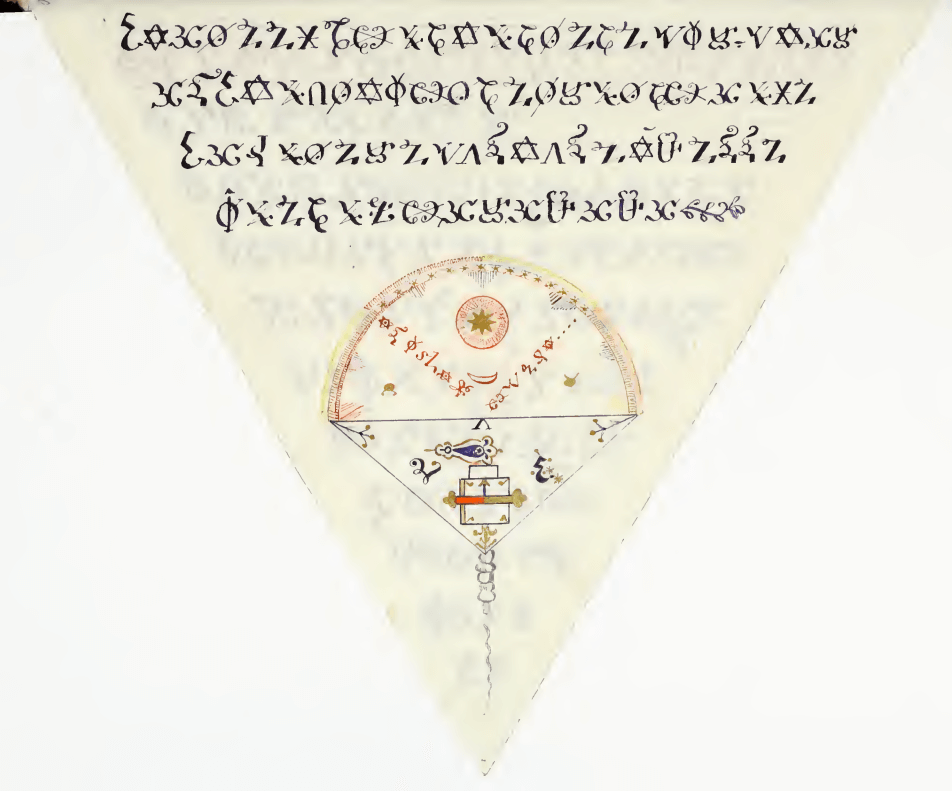

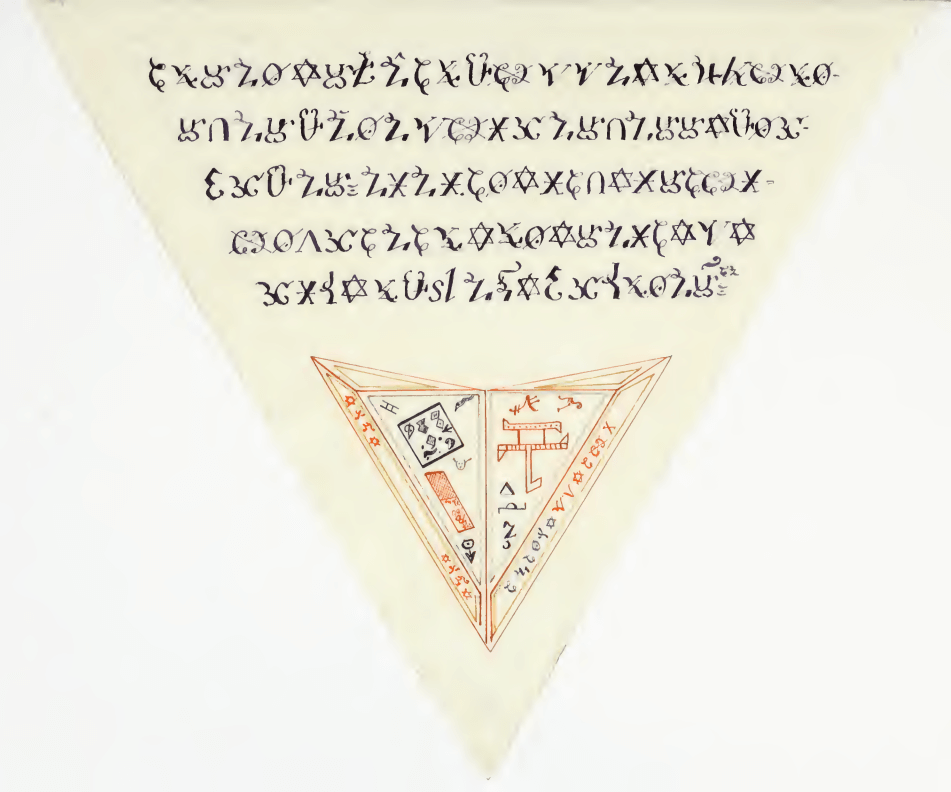

One gleams in red and gold triangles—MS 209 from the Manly P. Hall collection.

Another, MS 210, lies flat in notebook paper, the same words rewritten with nervous precision.

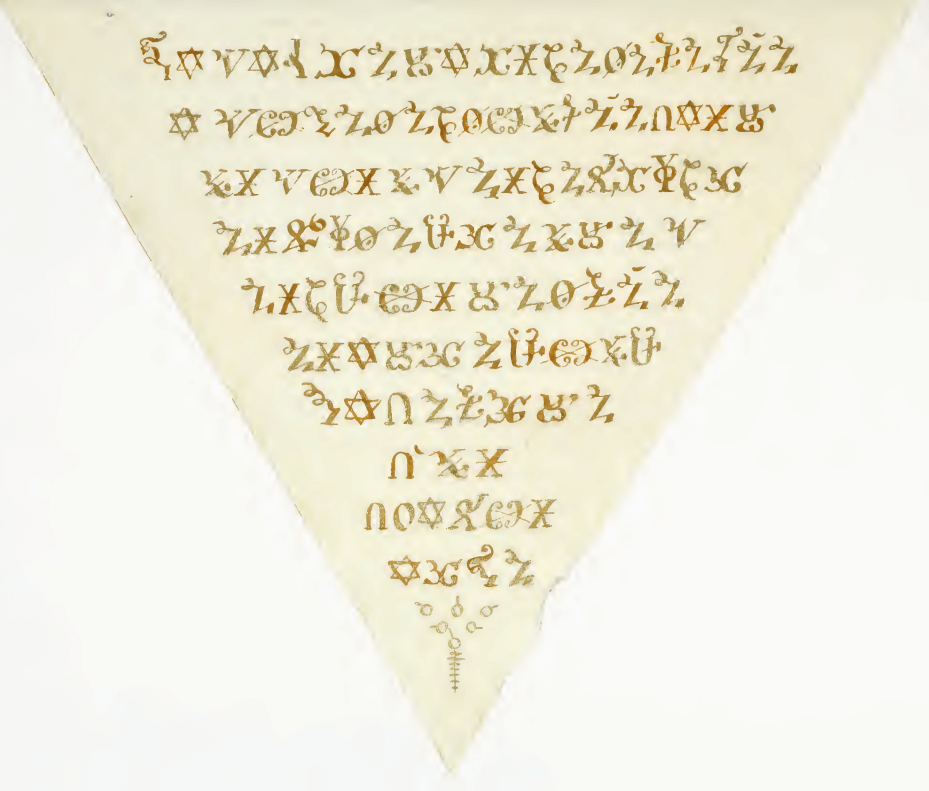

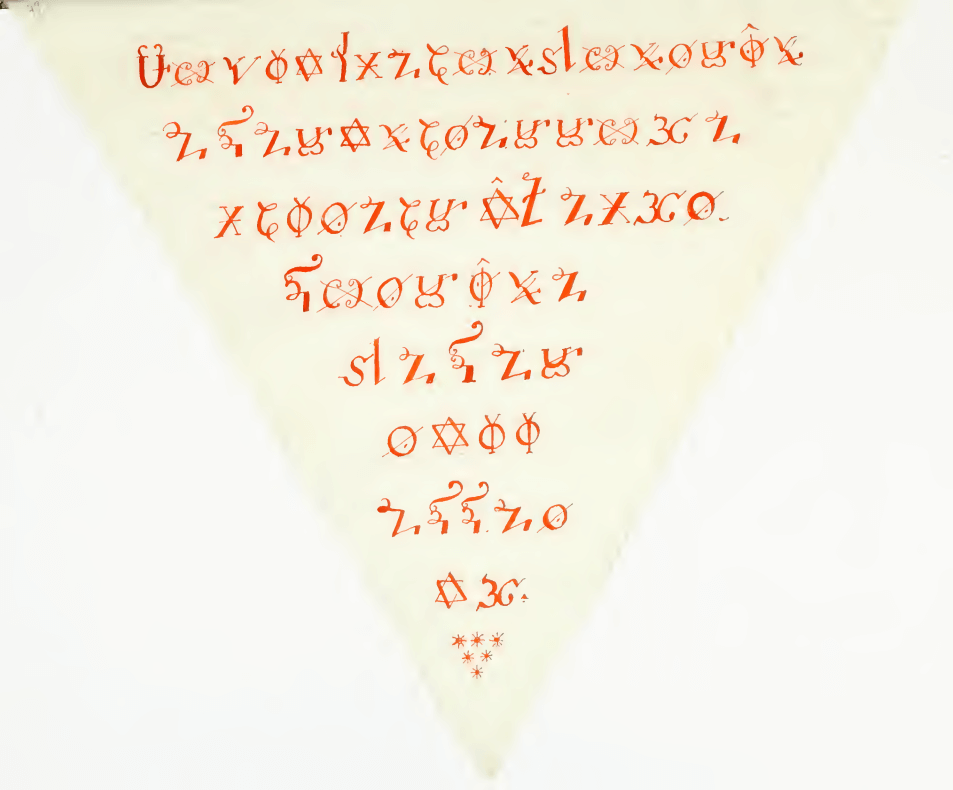

A third, Wellcome 4668 in London, is orderly and black-inked, its cipher letters neatly paired with their French equivalents, as if the writer were studying rather than invoking.

Placed side by side, they look like three voices singing one melody in different keys.

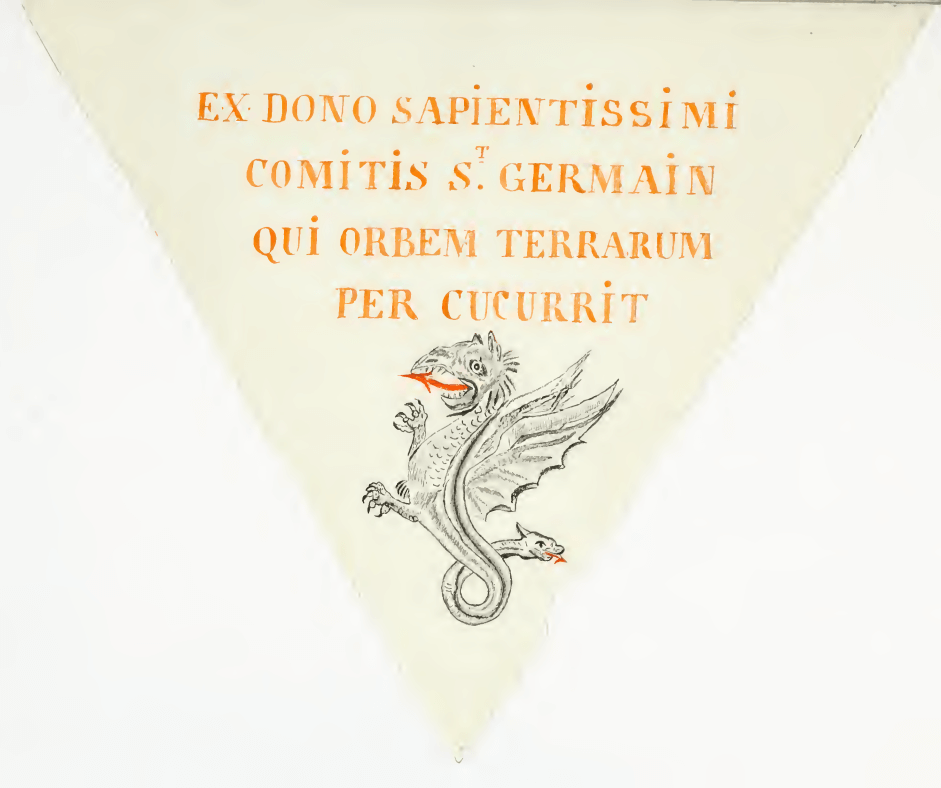

Their common origin is the enigma of the Count of Saint-Germain—the eighteenth-century polymath rumored to know every language and never to die.

If he truly mastered transmutation, he also mastered replication: each copy transforms yet preserves the same essence.

2. Provenance and Echo

MS 209 is the showpiece: cut to an equilateral form, written in gold, red, and brown, containing the dragon emblem and the invocation for treasure and longevity. It traveled from continental lodges into English bookshops, catalogued by Frank Hollings around 1930 and purchased later by Manly P. Hall for his library of Hermetic artifacts.

MS 210 surfaced only in notes by twentieth-century researcher Nick Koss. Slightly larger, rectangular, and less decorative, it preserves a complete cipher key on a separate leaf. The key assigns glyphs to French letters, with curious omissions: K and W have no symbols. Some letters—G, H, I, S, Y, and the contraction d’—appear twice, as if the scribe could not decide which form Saint-Germain intended.

The Wellcome 4668 manuscript in London bears the same structure but tidier execution. The script is less ornate, the key more systematic, and the marginalia include tentative translations. Someone was decoding rather than performing.

Taken together, the three manuscripts show a transmission chain: an original ritual codex copied by practitioners, studied by translators, and finally archived by collectors.

3. The Cipher’s Design

At first glance, the writing resembles an elegant shorthand—loops, hooks, and spirals flowing left to right. When transcribed, it yields eighteenth-century French sentences: “Nous invoquons Yalatina et Lemirot…” The underlying system is a simple substitution cipher, yet it carries stylistic layers of deliberate confusion. The symbols mimic Hebrew serifs and Greek curves, giving the impression of a sacred alphabet.

Each variant adjusts the cipher slightly, revealing both human error and creative intent:

-

In MS 210 the glyph for H resembles a coiled serpent; in Wellcome 4668 it stiffens into a rod.

-

The symbol for et (“and”) mutates from ornate ampersand to plain crossbar.

-

Where MS 209 writes NOTAMARGATET, another reads NOTAMMARGATEL—a single reversal that turns command into echo.

These differences matter less for meaning than for resonance. They demonstrate that the manuscript was copied by sight, not sound. The copyists did not always know the language they transcribed; they were tracing shapes whose power lay in their form, not their semantics.

4. Hands and Intention

To the historian, such discrepancies are evidence of multiple scribes.

To the initiate, they prove a subtler law: that no revelation survives intact; every transmission is a translation.

MS 209’s calligraphy feels ceremonial—slow, symmetrical, perhaps written in candlelight as a ritual act.

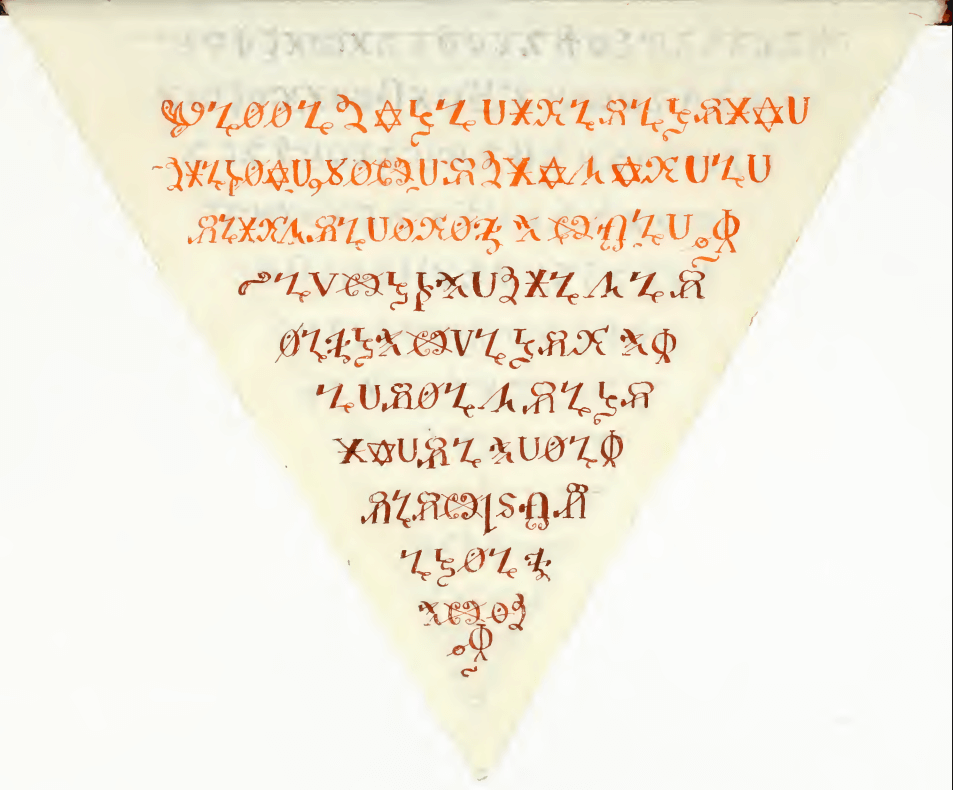

MS 210 reads as exercise: a student’s effort to reproduce each glyph faithfully, margins filled with corrections.

Wellcome 4668 is analytical—an Enlightenment mind cataloguing mystery.

These are the three hands of alchemy: the Adept, the Disciple, and the Scholar.

Each transforms the same text according to inner temperament.

In that sense, the manuscripts perform the doctrine they describe: solve et coagula—dissolve and recombine.

5. The Key that Wanders

None of the cipher keys is complete.

All omit the letters K and W, perhaps because eighteenth-century French rarely used them.

Each invents small deviations.

One adds a spiral symbol for per, later corrected to nom.

Another claims the ampersand means etc., until a later hand annotates, “non—cela veut dire et.”

The instability of the key hints that its custodians no longer understood the whole.

Yet such incompleteness might have been deliberate. In initiatory orders, knowledge was tiered: each degree revealed only part of the code so that meaning could never be possessed without context. The cipher itself became an initiation—error as gatekeeper.

6. From Code to Cosmos

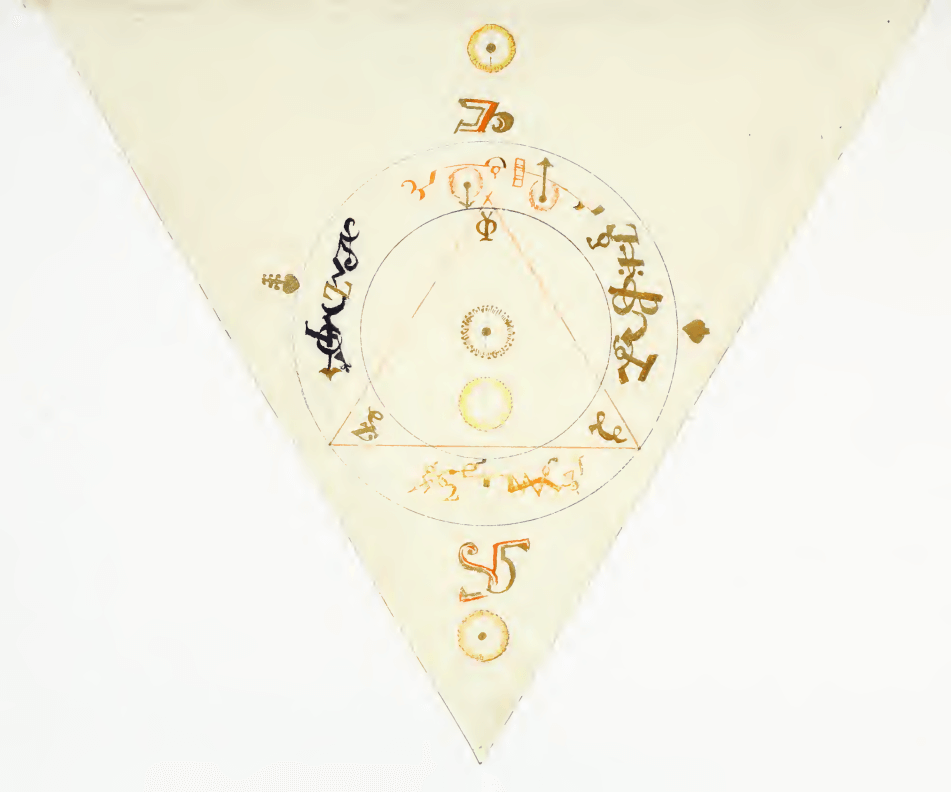

If one compares the pages themselves rather than the glyphs, another pattern emerges.

The spacing, the geometry, even the punctuation change according to temperament.

MS 209 breathes; its lines drift apart like chant.

Wellcome 4668 compresses; it rationalizes.

The difference between them mirrors the larger shift from mystical to mechanical Europe.

In that light, the cipher’s transmission reenacts the alchemical process it describes.

The golden text (MS 209) is the rubedo, the work perfected in fire.

MS 210’s hesitant pencil marks are the albedo, purification through reflection.

Wellcome 4668’s black ink is the nigredo, analysis that dissects the mystery to preserve it.

Three manuscripts, three colors, three phases of transformation.

7. The Problem of Authorship

Did Saint-Germain write any of them?

Handwriting analysis suggests that MS 209 and 210 share style but not the same penman.

The Wellcome copy is later.

If the Count composed the original, his followers preserved it with reverence but without understanding.

Saint-Germain was known to dictate rather than write. Contemporary reports describe him producing letters “without seeming to think,” then handing them off to be copied. This fits the manuscripts: an oral or visionary composition transmitted through amanuenses.

Thus the cipher may record not a solitary genius but a collaborative ritual—disciples writing in trance, guided by geometry.

8. Cipher as Initiation

Why encode a French text at all? Secrecy is too simple an answer.

A cipher alters consciousness. To read it requires patience, attention, rhythm.

In occult psychology, that sustained focus generates the very energy the ritual seeks.

Decoding becomes participation.

The scribes, struggling to remember which curve means S and which means G, enact the discipline of meditation.

Saint-Germain’s followers claimed that “the work is performed not in the furnace but in the mind.” The cipher externalizes that principle: comprehension as transmutation.

9. Comparative Examples

Consider a single phrase across the three copies—Bénis ce cercle (“bless this circle”).

In MS 209, the glyphs flow in a continuous arc, visually forming a circle themselves.

In MS 210, the letters separate, as if diagrammed for teaching.

In Wellcome 4668, the scribe writes the French translation in the margin, destroying symmetry but clarifying meaning.

One draws, one teaches, one defines.

The same motion occurs in alchemical diagrams of the period: original symbol → explicated chart → rationalized print.

The Triangular Book passes through those stages within its own lineage.

10. Linguistic DNA

When transcribed letter by letter, the three versions yield nearly identical content.

What varies is orthography—spelling and punctuation.

These small mutations function like DNA markers; they allow historians to reconstruct descent.

MS 209’s double t in NOTAMARGATET becomes single in later copies; therefore MS 209 precedes.

MS 210 corrects several contractions, then Wellcome 4668 regularizes spacing.

The chain moves from continental France to British empiricism, carrying the esoteric text into modern archive language.

Each copy reduces mystery a little more, yet each also ensures survival.

Alchemy’s paradox repeats: to preserve spirit, one must embody it.

11. Symbolic Reading

The three manuscripts can be read allegorically as stages of the same work.

-

MS 209 — Revelation: gold and red ink, fiery originality.

-

MS 210 — Reflection: student’s duplication, silvered mirror.

-

Wellcome 4668 — Fixation: black ink, crystallized knowledge.

In the Great Work, these correspond to sulfur, mercury, and salt—the volatile, the mediating, the fixed.

Thus the manuscripts collectively form an alchemical trilogy, whether or not their custodians intended it.

Each time the cipher changed hand, it embodied a phase of the process it describes.

12. The Philosophy of Variation

Variation was once regarded as corruption; modern semiotics sees it as life.

A language that never changes dies.

By existing in three imperfect forms, the Saint-Germain cipher demonstrates resilience through mutation.

Its changing glyphs enact the doctrine inscribed within: “to preserve health and prolong life for a century.”

For a manuscript, longevity is achieved by reproduction, not stasis.

Saint-Germain’s immortality, then, lies in transmissibility.

Each scribe became a cell dividing, imperfectly yet continuously.

The text lives because it refuses to be final.

13. The Scholar’s Paradox

Modern researchers seeking the “true” version risk repeating the Wellcome scribe’s error—believing that decoding ends the mystery.

But Saint-Germain’s own legend warns otherwise: understanding without wonder kills the work.

The cipher’s very inconsistencies may be the safeguard that prevents dissection from replacing devotion.

As long as the letters differ, meaning remains alive.

Therefore the most faithful restoration might be a digital palimpsest that overlays all three, preserving discrepancy as luminous vibration—a visible chorus of difference.

14. Transmission and Myth

By tracing these copies, we also trace how Saint-Germain himself transformed from historical polymath into mythic immortal.

The manuscripts show no obsession with endless life; they speak of health, purity, proportion.

Yet as their copies multiplied, so did exaggeration.

Readers mistook “a century with the freshness of fifty” for eternity.

In the same way, scribes mistook variant symbols for mistakes instead of metaphors.

Every repetition added one more layer of myth until the Count’s mortality disappeared beneath his handwriting.

Thus the three hands do not merely transmit a text—they manufacture the legend.

15. The Geometry of Survival

Lay the three manuscripts in a triangle: 209 to the south (fire), 210 to the west (water), 4668 to the north (earth).

Their meeting point in imagination becomes air—the living breath of interpretation.

At that intersection, the cipher revives.

Each modern reader who attempts to decode it becomes the fourth element completing the square, turning theory back into life.

This is the secret symmetry behind Saint-Germain’s geometry: immortality is not endless duration but perpetual participation. A work lives as long as someone is willing to translate it again.

16. Closing Reflection

In the faint red ink of MS 209’s last page three stars shimmer above the word Finis.

Seen beside the other copies, the stars signify not ending but replication—three sources, three continuations.

The cipher did what its ritual promised: it found treasure in the earth of language and prolonged its own life beyond a century.

Saint-Germain’s disciples may have failed to reproduce his exact letters, but they succeeded in the deeper operation: to keep the work breathing.

Through variation, it achieved equilibrium; through imperfection, permanence.

Every error is an act of preservation; every copy, a new incarnation.

That is the final mystery of the Triangular Book:

The cipher lives because it never settles, and in its restless geometry the Count of Saint-Germain remains—

not immortal, but unending.

Sources & Provenance (Manuscript Comparison)

MS 209 — Getty (Manly P. Hall Collection)

- Format: Triangular codex; red & gold inks; complete ritual with figures.

- Use in this article: Primary visual and textual witness; baseline for glyph shapes.

- Notes: Finis page with three stars; circle and triangle diagrams match the operative rubric.

MS 210 — Private Collection (cited by Nick Koss)

- Format: Rectangular folio; includes a cipher key; cleaner, standardized glyphs.

- Use in this article: Collation of letterforms; confirms several readings; some omissions.

- Notes: Secondary symbols for H and contraction d’ appear in the key but not in text.

Wellcome MS 4668 — Wellcome Collection, London

- Format: Neat cipher key + marginal French/English notes; study copy.

- Use in this article: Linguistic control; shows corrections (e.g., “et” vs. “etc.”; “nom” vs. “per”).

- Notes: Orders symbols by glyph→Latin letter; helpful for normalization across copies.

Method: Readings were established against MS 209, then checked against MS 210 and Wellcome 4668. Where witnesses conflict, the majority reading or best paleographic match is preferred; divergences are noted inline.

References & Further Reading

- The Triangular Book of St. Germain, Ouroboros Press, 2014 — primary comparative edition featuring MS 209, MS 210, and Wellcome 4668.

- Wellcome Collection, MS 4668 — contains cipher key and alternate readings.

- Getty Research Institute, MS 209 — gold and red ink triangular codex.

- Manly P. Hall, Secret Teachings of All Ages (1928) — contextual notes on the Count of St. Germain.

- Esoteric Archives, Alchemical Texts Index — reference for parallels in 18th-century ritual manuscripts.

- Klossowski de Rola, Stanislas, Alchemy: The Secret Art (Thames & Hudson, 1973).