The Saint-Germain Circle: Hermetic Networks of the Eighteenth Century

The Saint-Germain Circle: Hermetic Networks of the Eighteenth Century

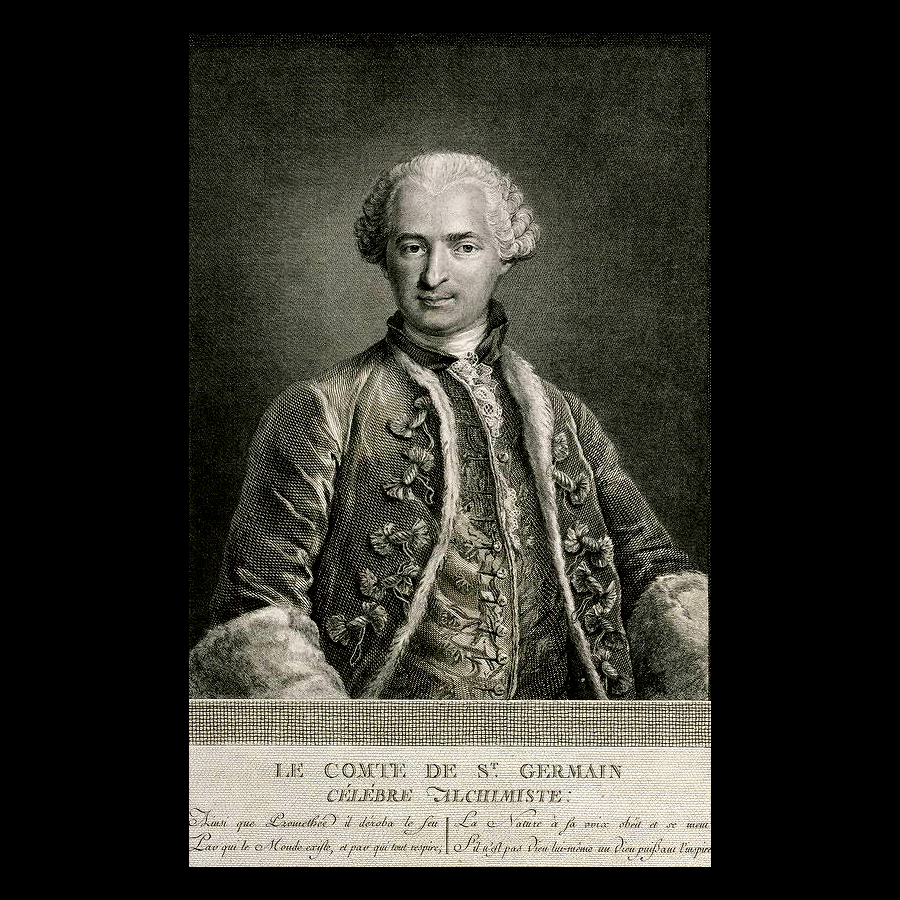

1. Introduction – Between Legend and History

The Comte de Saint-Germain is one of the most persistent figures in European occult history. Contemporary letters and diplomatic records confirm his presence at courts across Europe between 1740 and 1780, yet his origins and end remain uncertain. Later generations turned him into a mythic “immortal adept.” Behind that legend stands a small but identifiable community of nobles, Freemasons, and scholars who shared his interests in alchemy, symbolism, and moral reform. Modern historians describe this environment as the Saint-Germain Circle—a loose, transnational network operating in the final decades of the Enlightenment.

2. Composition and Geography

The circle was not a formal order. It functioned as a salon of initiates joined by correspondence and occasional visits rather than oaths or charters. Its main centers were Paris, Leipzig, Vienna, and Venice, with links to St. Petersburg and Copenhagen.

Known participants included:

-

Prince Karl of Hesse-Kassel (1744–1836): governor of Schleswig-Holstein and Saint-Germain’s final host; he maintained an alchemical laboratory and preserved many of the Count’s papers.

-

Louis-Claude de Saint-Martin (1743–1803): the “Unknown Philosopher,” whose writings on interior regeneration paralleled the Count’s teaching.

-

Antoine-Joseph Pernety (1716–1796): Benedictine scholar and founder of the Avignon Society, which circulated Hermetic manuscripts and defended spiritual alchemy.

-

Giuseppe Balsamo (Count Cagliostro): the controversial magician whose “Egyptian Rite” of Masonry shows close structural parallels to the Triangular Book ritual.

These figures did not form a single hierarchy but recognized one another as peers pursuing a unified goal: the recovery of the “sacred science” believed to underlie religion and nature alike.

3. Shared Doctrine

Across their writings and manuscripts certain principles recur:

-

Alchemy as moral and spiritual regeneration. The transmutation of metals was treated as a metaphor for purification of the soul.

-

Geometry and proportion as divine language. Diagrams such as circles, triangles, and decagrams were used to represent cosmic order.

-

Theurgy through sacred names. Invocation, rather than sacrifice, was considered a disciplined method for aligning the human will with divine intelligence.

-

Secrecy by cipher. French texts rendered in symbolic alphabets protected meaning while signifying initiation.

These ideas were compatible with late-Enlightenment Masonry and the Rosicrucian revival. Members of the circle often held Masonic rank but emphasized mysticism over fraternal politics.

4. Texts and Instruments

The most distinctive artifact associated with the circle is the Triangular Book of Saint-Germain (MS 209, Manly P. Hall Collection, Getty Research Institute). Written in red and gold cipher on triangular pages, it combines geometry, invocation, and a three-fold ritual concerning lost treasures, hidden metals, and the prolongation of life. Its execution is of professional quality and shows no signs of practical use, indicating that it served as a ritual exemplar or initiatory display copy.

Comparable documents include:

-

La Très Sainte Trinosophie (attributed to Saint-Germain or Cagliostro), a visionary allegory structured in twelve symbolic chambers.

-

Philosophical Mercury and Clavis Artis, both combining chemical instruction with moral allegory.

Together these texts illustrate how the circle attempted to merge classical Hermeticism with contemporary Enlightenment rationality—an effort to preserve spiritual science without rejecting reason.

5. Function and Purpose

Within its own context the Saint-Germain Circle acted as a research lodge and spiritual reform movement. Participants met in private libraries and laboratories to compare translations of ancient treatises, test chemical experiments, and discuss metaphysical doctrine. The Count’s teaching emphasized moderation, charity, and the perfection of the human body as an instrument of spirit. Political neutrality was a principle: many members served opposing courts but maintained correspondence on scientific and philosophical matters.

The underlying objective was the restoration of the “lost harmony”—a synthesis of religion, science, and art that the adepts believed had existed before the divisions of modernity. Their use of triangles, circles, and mirrored operations expressed this goal in visual form.

6. Decline and Dispersal

After 1784, reports of Saint-Germain’s death in Schleswig marked the circle’s gradual dissolution. The French Revolution destroyed its aristocratic base, and most surviving members either went into exile or turned their lodges into philosophical societies. Yet the manuscripts endured. During the 19th century their ideas resurfaced through Eliphas Lévi, Papus (Gérard Encausse), and Stanislas de Guaita, who built the modern French occult revival on similar principles of inner alchemy.

Manly P. Hall’s acquisition of MS 209 in the 20th century ensured the physical survival of at least one authentic specimen of the circle’s work. It remains the most tangible link between the historical Count and his later legend.

7. Legacy and Continuity

Elements of the Saint-Germain synthesis persist in several modern traditions:

-

Rosicrucian and Martinist orders that stress moral purification and contemplative practice.

-

Esoteric Masonry, particularly Scottish and Egyptian Rites preserving Hermetic symbolism.

-

Theosophical and New Thought movements, which reinterpreted Saint-Germain as an ascended teacher rather than a historical person.

These later adaptations altered the theology but retained the same central proposition—that consciousness can participate directly in the creative intelligence of nature.

8. Conclusion

The Saint-Germain Circle represents the final flowering of the Hermetic-Masonic experiment before modern secular science took its place. Its members stood at the intersection of aristocratic culture, empirical investigation, and mystical aspiration. Their surviving manuscripts, especially the Triangular Book, provide rare evidence that the pursuit of hidden knowledge was not a marginal superstition but a disciplined branch of Enlightenment thought. Understanding their network restores historical depth to the figure of Saint-Germain and shows how his legend emerged from a genuine intellectual movement that sought light through geometry, language, and inward transformation.

References & Further Reading

- Yates, Frances A., The Rosicrucian Enlightenment (Routledge, 1972) — on Hermetic-Masonic networks influencing Saint-Germain’s era.

- Churton, Tobias, The Magus of Freemasonry (Inner Traditions, 2006) — on Saint-Germain and Enlightenment esoteric circles.

- Klossowski de Rola, Stanislas, Alchemy: The Secret Art (Thames & Hudson, 1973) — on ritual diagrams and symbolic geometry.

- Waite, A.E., The Real History of the Rosicrucians (1887) — contextualizes Saint-Germain within the later Rosicrucian revival.

- Philosophical Research Society Archive, prs.org — biographical holdings on Manly P. Hall and Saint-Germain research.

Links

Table