The Triangular Book of Saint-Germain: Ritual Geometry and the Legend of Immortality

1. The Dragon’s Gift

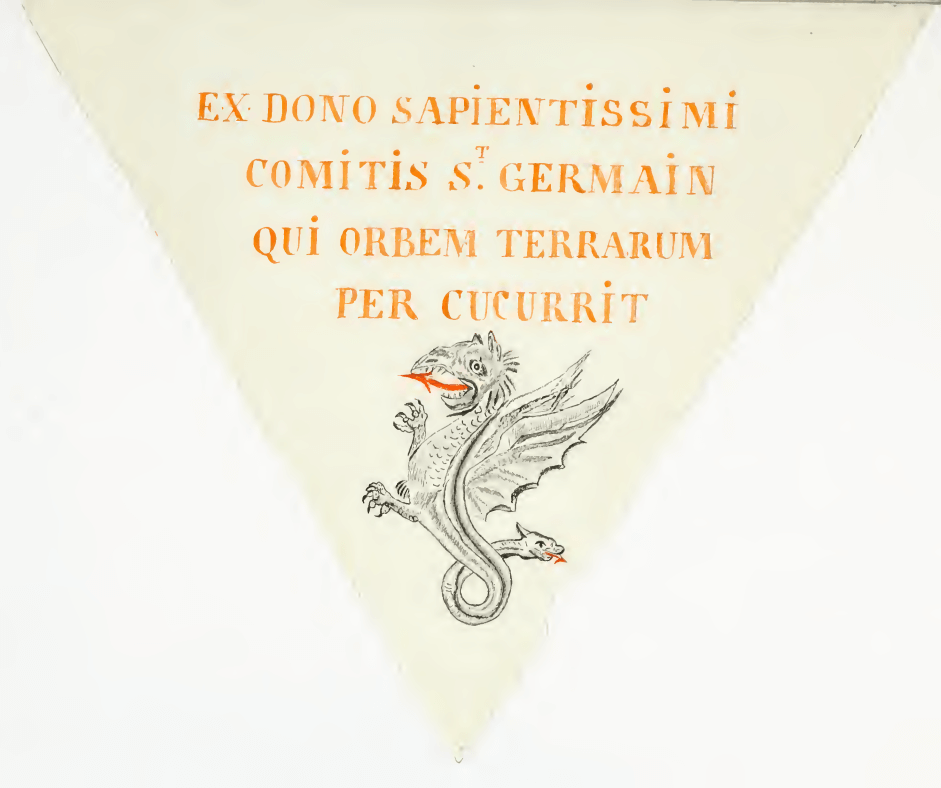

A dragon coils across the parchment, wings poised as if to lift the page itself.

Beneath it, the Latin words Ex Dono Sapientissimi Comitis St. Germain Qui Orbem Terrarum Per Cucurrit announce the manuscript’s donor: “A gift from the wisest Count of Saint-Germain, who has travelled the world.”

The phrase functions like a magical key. It opens the Triangular Book of Saint-Germain, known in the Getty Research Institute as MS 209, an eighteenth-century cipher manuscript written in gold, red, and brown inks, bound in a triangular form, and attributed to the most elusive adept of the Enlightenment. The Count—composer, linguist, chemist, reputed immortal—bequeathed Europe a legend that blurred the line between alchemy and myth. This small triangular codex became the physical embodiment of that legend: a geometry of secrecy, a mirror of his claimed immortality.

2. Provenance and Context

MS 209 rests today in the Manly P. Hall collection, Los Angeles, labeled “Triangular Book of Saint Germain.” Its provenance traces back through rare-book dealer Frank Hollings of High Holborn, London, whose 1930s catalogue described “a very rare magical manuscript written in cipher, in French, 47 pages, 3 magical diagrams, the whole cut to a triangular shape.” Before Hall acquired it, the codex passed through the hands of European Masonic collectors linked to Antoine Louis Moret—a name inscribed inside the original binding. Each stage reinforced its aura: part Hermetic relic, part Rosicrucian curiosity.

In the same period, other triangular manuscripts circulated—copies or descendants bearing similar ciphers and invocations. They point toward a milieu of late-Enlightenment occult masonry, where alchemical texts were recast as ritual manuals. The Triangular Book stands at the meeting of two eras: the fading laboratory tradition of transmutation and the emerging interior alchemy of will and word.

3. The Architecture of Mystery

The manuscript’s triangular format is not ornamental. The triangle was the philosopher’s shorthand for manifestation—three angles of the One: salt, sulfur, mercury; body, soul, spirit; birth, life, death. To write within that shape is to declare that geometry itself participates in revelation.

Every page radiates careful construction. Lines of cipher text form equilateral borders; inner symbols spiral toward invisible centers. Ink color alternates with purpose:

– Gold for illumination and solar force.

– Red for the life-blood of the operation.

– Brown or black for grounding, the material substrate.

There are three figures:

-

The title leaf (dragon and dedication).

-

The ritual circle, composed of concentric orbits.

-

The inner triangle, filled with sigils and sacred names.

Each figure doubles as instruction. Where later alchemical treatises describe the vessel, the Triangular Book draws it. The manuscript becomes both text and tool, the circle itself a furnace of invocation.

4. The Cipher

The writing system appears at first glance to be a form of reversed Latin script ornamented with curvilinear marks. Triangularbook.com and surviving MS 210 / Wellcome 4668 keys reveal that the cipher substitutes unique glyphs for French letters and contractions such as d’ and per. Yet the keys disagree—each slightly incomplete, suggesting independent attempts to copy without full understanding.

Nick Koss’s modern analysis shows that the cipher can be solved into French phrasing, later translated by Robert Word (1979). The translation reads like a ritual manual rather than a philosophical treatise: an operation for finding lost treasures, discovering metals and gems, and extending life to one hundred years “with the freshness of fifty.” The voice alternates between command and prayer—an operator addressing “spirits who preside over the hours of the night.”

From a linguistic standpoint, the cipher’s structure shows eighteenth-century French syntax consistent with occult Masonic circles, not medieval alchemy. Its secrecy is performative: a way to encode sanctity, not to conceal technical knowledge.

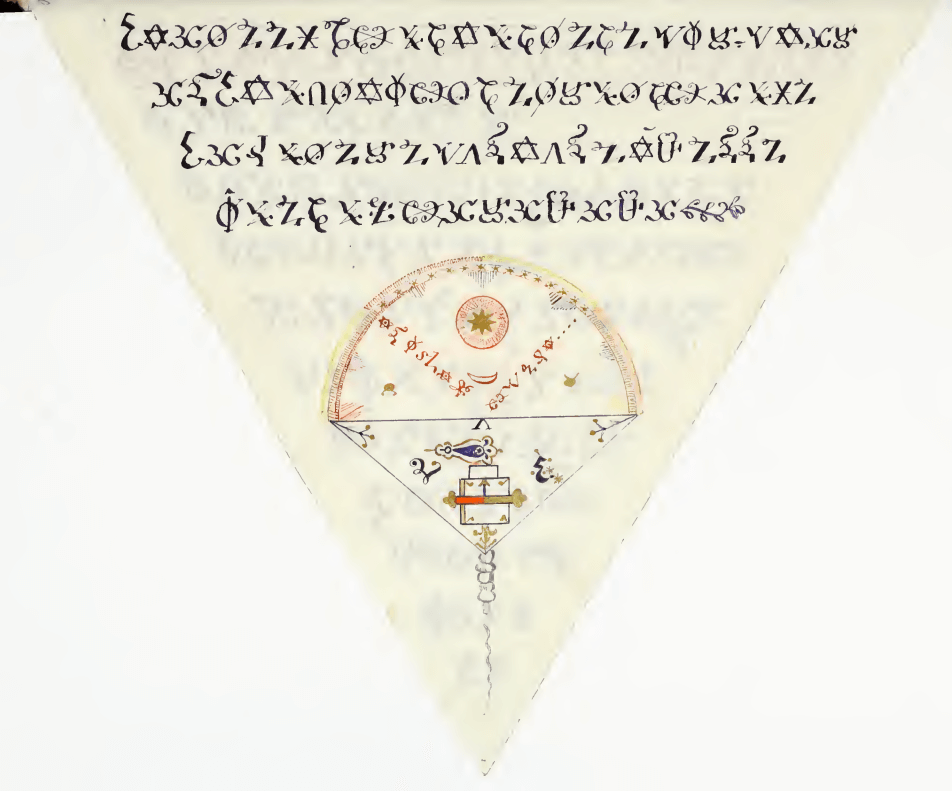

5. The Ritual Geometry

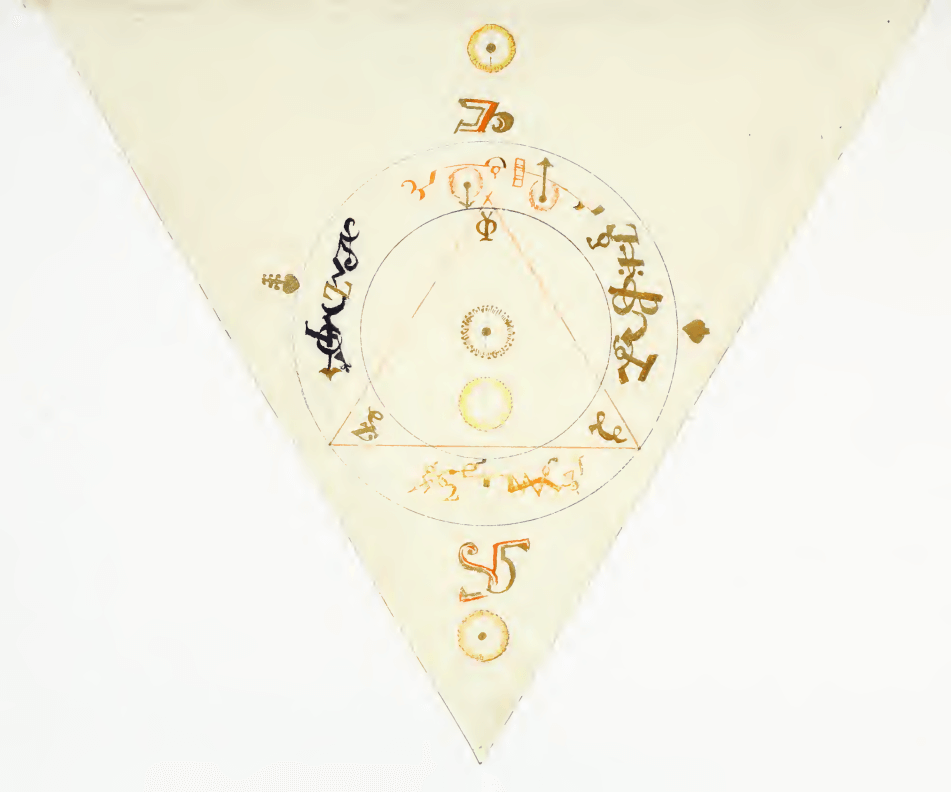

The central diagram—two concentric circles crossed by a triangle—serves as the stage. The instructions divide space between the operator and the Levite (assistant). Each stands within a consecrated circle: the smaller for the adept, the outer for the supporting voice.

The operator enters bearing a figure—a talisman to be worn upon the head during invocation. The text prescribes blessings of fire, incense, and lamps, invoking divine names such as NOTAMARGATET, YANODA, MIOLE, and SORIDIS. The orientation of directions—east, west, high, and low—corresponds to astrological quadrants. The east hosts LEAMAN, LECIAB, LATRANAVIO, RIBRAL, TELARO; the west mirrors them with ELANA, LEPAB, USTAEL, THAERRUB, SOTARECO, ILIBAPAC.

This symmetrical distribution turns the page itself into a map of the heavens. The operation begins when sun, earth, and moon align in conjunction—a celestial equilibrium echoing the chemical conjunction of alchemy. The final gesture—placing the figure upon the head, listening to “what the aerial spirits whisper”—translates the laboratory’s sublimation into a contemplative act. The transmutation has moved from furnace to imagination.

6. The Invocation

The invocation is a litany of names alternating between Hebrew, Latin, and unknown syllables. Its rhythm resembles theurgy more than magic—petition through vibration.

A few lines capture its spirit:

“We invoke you Yalatina, Lemirot, Lesiab, Telar… we command you by Him by whom all things were made… let me know, by a just inspiration, where there are mines of gold and silver, and how life may be prolonged in health for a century.”

These words transform material ambition into a spiritual request. The adept asks not only for treasure but for purity sufficient to receive inspiration. The promise of physical gold becomes a metaphor for revealed knowledge.

The closing formula seals the act:

“In the name of the Eternal, my God, true master of my body, my soul, and my spirit — go in peace, be ever ready when I shall call you.”

Three stars follow—Finis rendered as constellation.

7. The Philosopher’s Logic

Why did Saint-Germain—or his circle—encode a text so unlike the chemical recipes of earlier alchemists? Because by the eighteenth century, the Stone had migrated inward. To prolong life “for a century with the freshness of fifty” no longer meant ingesting an elixir but harmonizing the triad of mind, body, and spirit—the tria prima recast as a psychosomatic formula. The triangle of the manuscript thus mirrors Paracelsus’s doctrine of Vita Prima Tria, the three vital principles.

The invocation’s dual aims—discovering metals and preserving health—repeat the two halves of the Great Work:

-

Lesser Work: mastery of matter (the metallic transformation).

-

Greater Work: mastery of the self (the elixir of life).

In both, the operative force is the Word, the vibration of divine names—the modern descendant of the Logos that “spoke light into being.” The Triangular Book turns the laboratory into liturgy.

8. Between Myth and Manuscript

The Count of Saint-Germain stands at the border of Enlightenment rationality and Hermetic imagination. His contemporaries—Voltaire, Casanova, Madame de Pompadour—spoke of him with equal fascination and skepticism. Some saw a charlatan chemist; others, a messenger of hidden wisdom. In Masonic legend, he becomes the wandering adept who appears in every century unchanged, teaching kings and initiates the art of transmutation.

The Triangular Book feeds that legend by existing. Its craftsmanship, triangular pages, and flawless hand seem impossible to forge without anachronistic precision. Each letter is consistent; no corrections mar the cipher. Even skeptics admit the handwriting shows almost superhuman control. To hold the manuscript is to feel that its author—whoever he was—understood perfection as discipline incarnate.

9. The Geometry of Immortality

The triangle is the simplest shape that can contain space. In sacred geometry it represents the first act of manifestation—the One reflected as Two, reconciled as Three. Every operation in the manuscript reenacts that law. The adept’s circle mirrors heaven; the Levite’s circle mirrors earth; their union within the triangle births the work. Immortality here is not endless duration but equilibrium: when spirit, soul, and body stand in exact proportion, the flow of decay halts.

This is why the manuscript insists on conjunction—sun, moon, and earth in one line. The cosmic alignment externalizes the internal one. The operator who harmonizes with that pattern becomes a microcosm of conjunction, achieving what the old texts called the fixation of the volatile—the stabilization of life-force.

10. The Cipher as Mirror

Decoding the text today teaches a second lesson: secrecy itself is transformative. To engage a cipher is to train perception, to move from seeing to understanding. The reader becomes participant. Each symbol demands contemplation, every curved letter a meditation on hidden correspondence. The manuscript’s encryption therefore functions as an initiatory veil. The act of reading becomes the alchemy.

Those who expect chemical formulas find prayer; those who seek prayer discover geometry. The text deflects literalism, insisting that truth must be earned by patience of the eye.

11. Parallels and Echoes

Across the centuries, echoes of the Triangular Book resurface in later works:

-

The Book of Aquarius (2011) reclaims the Stone as an interior revelation accessible to all—a digital descendant of Saint-Germain’s triangle.

-

The Rosicrucian manifestos had already joined chemical and spiritual regeneration, declaring that true gold is “wisdom perfected.”

-

In Paracelsian medicine, disease arises from imbalance among the three principles; the Triangular Book transforms that diagnostic triad into a rite of cosmic proportion.

Thus, MS 209 stands as bridge between Paracelsus’s tria prima and the twentieth-century esoteric revival under Manly Hall. Hall himself considered it proof that “alchemy never died; it changed its handwriting.”

12. The Modern Reader

To modern eyes, the manuscript’s promises—treasure, youth, communion with spirits—appear symbolic, even theatrical. Yet its enduring fascination suggests that readers still sense something authentic behind the artifice: the intuition that life may be extended not by chemistry but by comprehension of order.

To read the Triangular Book today is to encounter the Enlightenment’s shadow, the point where reason touched mystery and found it familiar. The text does not ask for belief; it demands attention. It reminds us that every geometry is also a prayer.

13. Closing Aphorism

At the manuscript’s end, three stars glimmer above the final line like sparks preserved from the dragon’s mouth. They signify completion, the triune seal of the work. If the Triangular Book contains any true elixir, it lies in the discipline of its construction—the patient alignment of symbol and word, ink and breath. Through that geometry, Saint-Germain’s immortality persists: not as endless years, but as the unbroken equilibrium between mystery and form.

To live within the triangle is to remember that perfection is not duration, but proportion.

Figures and Provenance

Figure 1 – Title Page (“Ex Dono Sapientissimi”)

- Source: MS 209, Manly P. Hall Collection, Getty Research Institute.

- Description: Latin dedication beneath the winged dragon emblem; opening of the codex establishing Saint Germain’s authorship and emblem of wisdom.

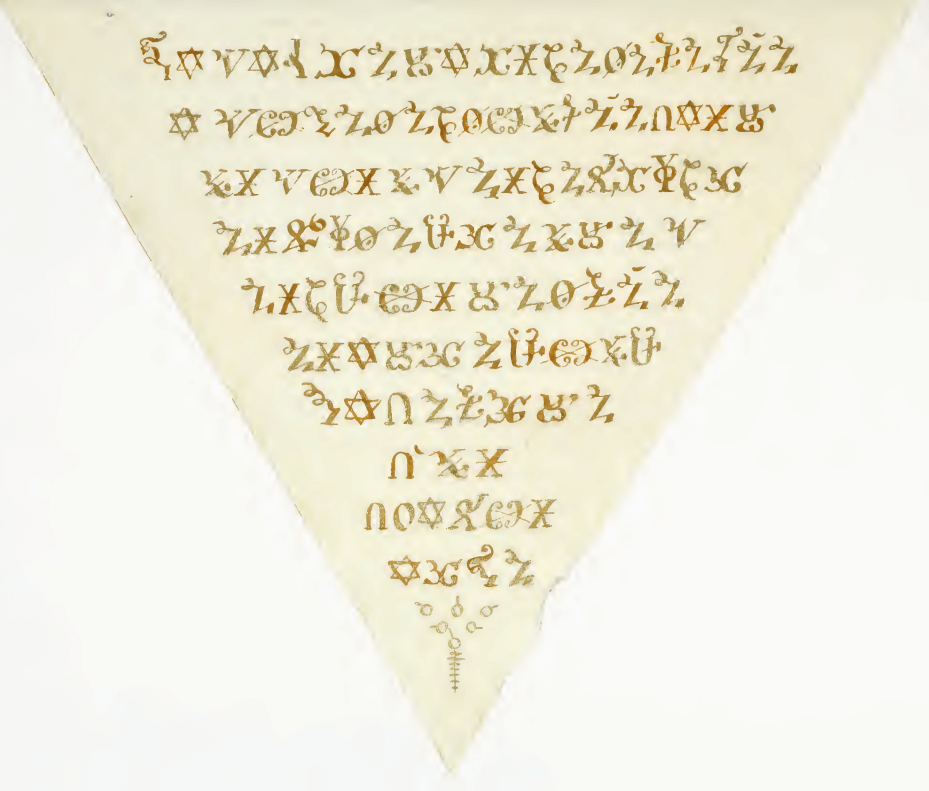

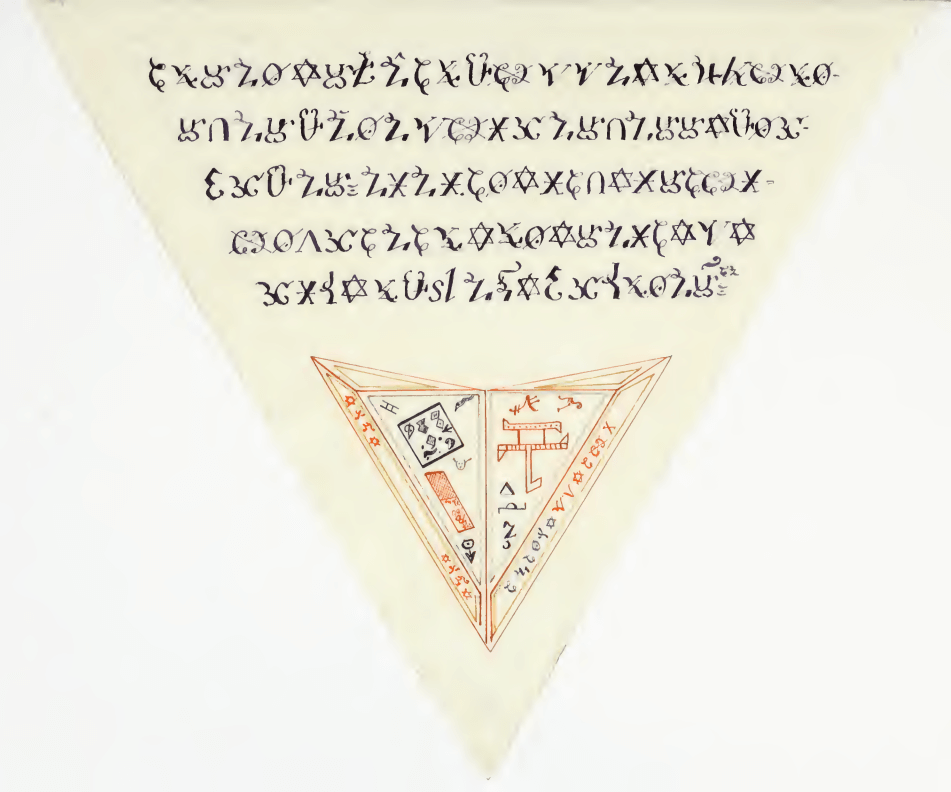

Figure 2 – Invocation Opening

- Source: MS 209 (Triangular Book of Saint-Germain).

- Description: First block of gold-ink cipher initiating the ritual sequence and timing instructions for conjunction of Sun, Moon, and Earth.

Figure 3 – Inner Circle Diagram

- Source: MS 209.

- Description: Concentric circles and sigils defining the operator’s and Levite’s stations within the ceremony; early geometric representation of ritual space.

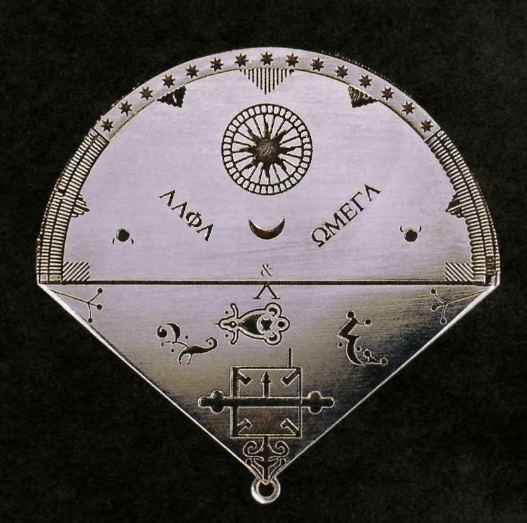

Figure 4 – Triangular Diagram of Operation

- Source: MS 209.

- Description: Equilateral triangle filled with emblematic instruments and cipher glyphs; symbolizes the alchemist’s inner vessel and balance of three principles.

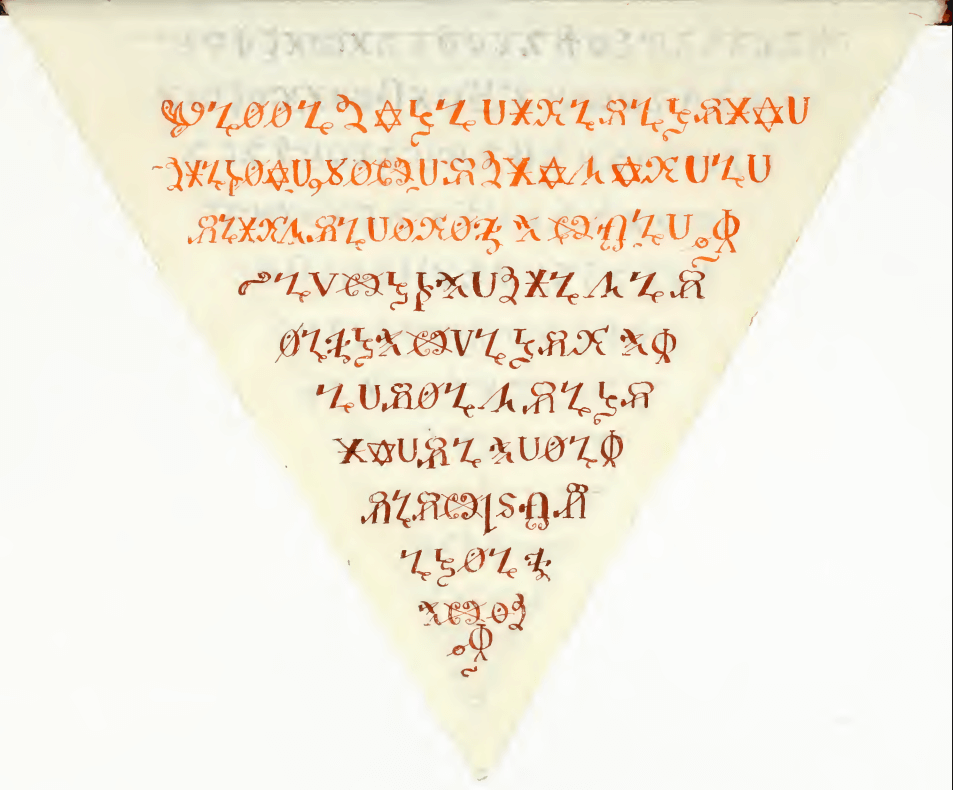

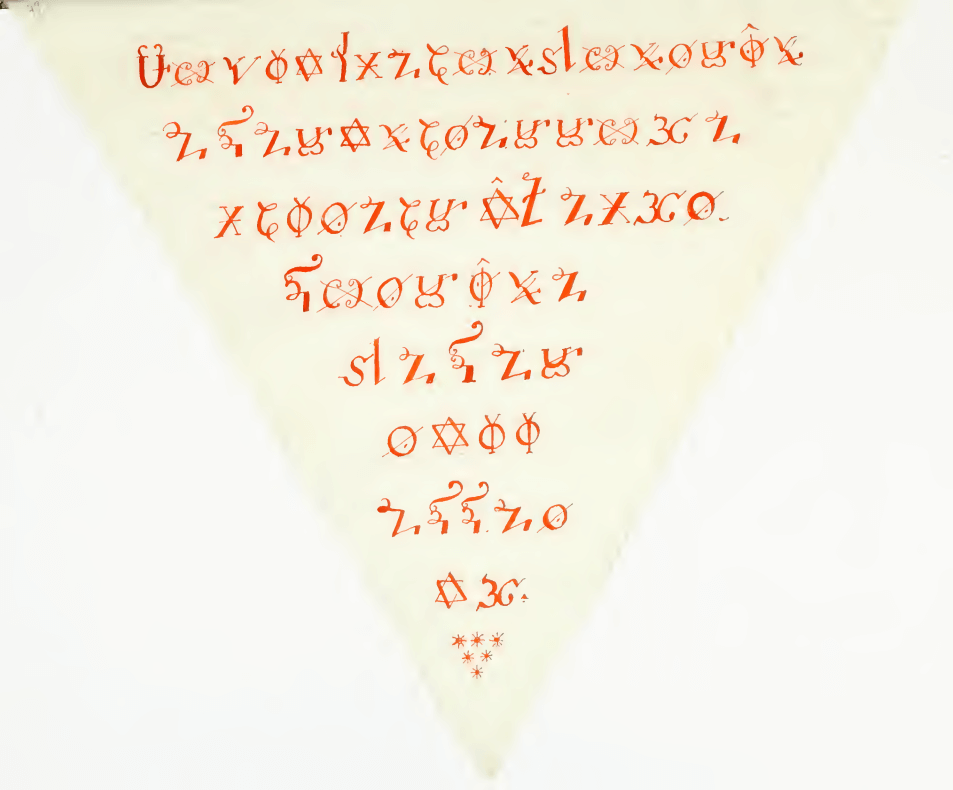

Figure 5 – Invocation Continuation

- Source: MS 210 (Nick Koss reference).

- Description: Parallel folio preserving later lines of the invocation; cleaner penmanship shows transition from liturgical tone to direct command of spirits.

Figure 6 – Cipher Key Comparison

- Source: Wellcome MS 4668 (London).

- Description: Alphabetic key aligning cipher glyphs with French letters; includes pencil corrections for et/etc. and nom/per; essential for modern decipherment.

Figure 7 – Finis Page (“Triangle of Stars”)

- Source: MS 209.

- Description: Closing red cipher beneath a triple-star seal; marks completion of the ritual cycle and closure of the vessel.

Note: All images drawn from manuscript witnesses held by the Getty Research Institute and comparative copies cited by Nick Koss and the Wellcome Collection. Captions follow archival order and preserve manuscript spelling conventions.

References & Further Reading

- The Triangular Book of St. Germain, Ouroboros Press, 2014. Annotated edition with introduction and cipher analysis. triangularbook.com.

- Getty Research Institute, Manly P. Hall Collection (MS 209) — original triangular manuscript facsimile.

- Wellcome Collection, MS 4668 — alternate copy with cipher key and English marginalia.

- Nick Koss, Triangular Book of St. Germain, Ouroboros Press (translator and editor’s notes), 2014.

- Waite, A.E., The Hermetic Museum (1893). Archive edition via Archive.org.

- Yates, Frances A., The Rosicrucian Enlightenment (Routledge, 1972) — background on 17th–18th century Hermetic networks.