Salomon Trismosin

Dr. Stephen Skinner (Author),

Dr Rafal T. Prinke (Author),

Georgiana Hedesan (Author),

Joscelyn Godwin (Author)

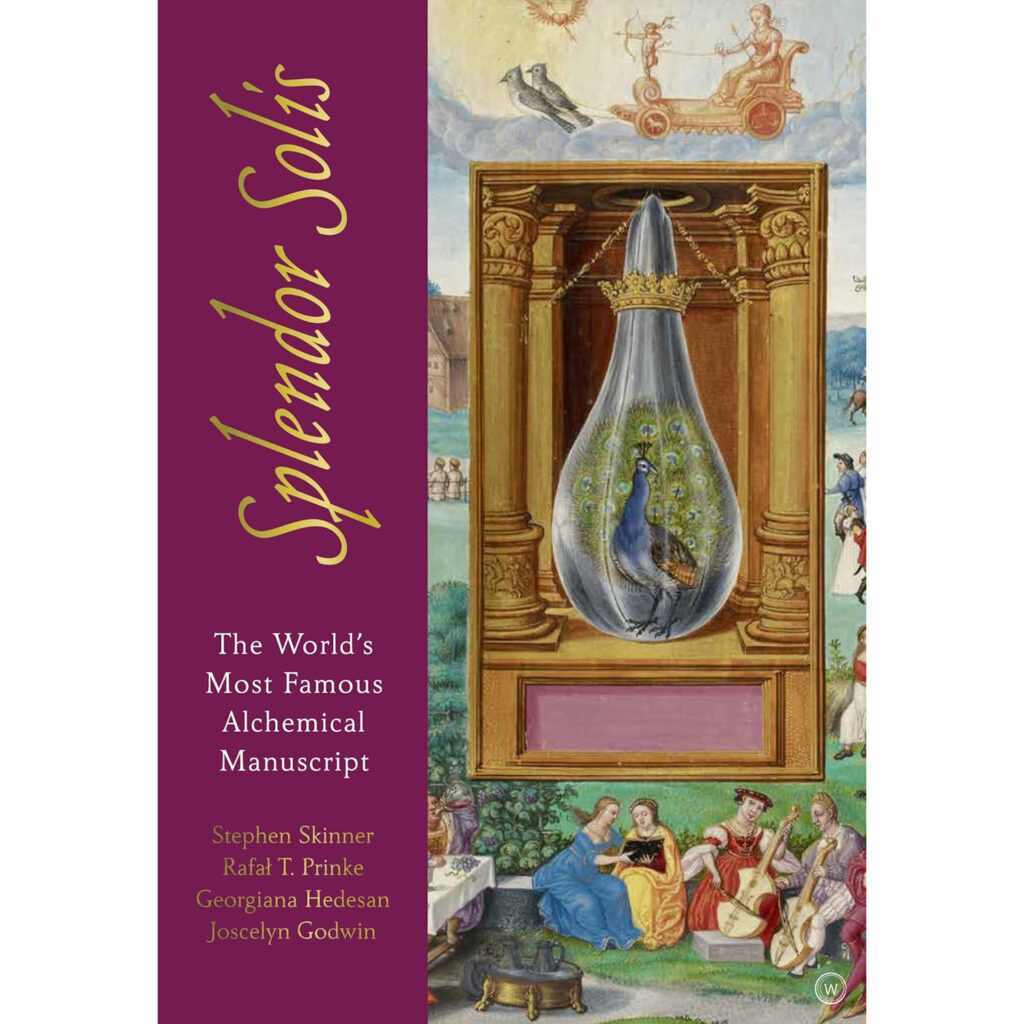

Review of Splendor Solis: The World’s Most Famous Alchemical Manuscript

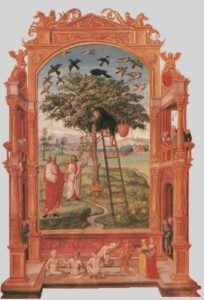

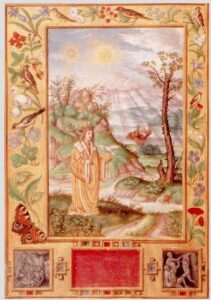

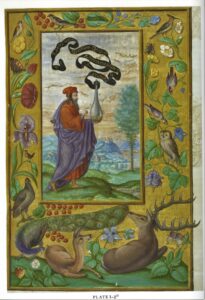

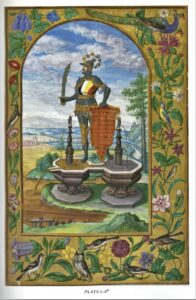

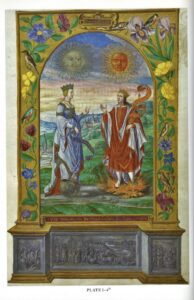

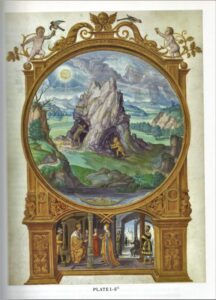

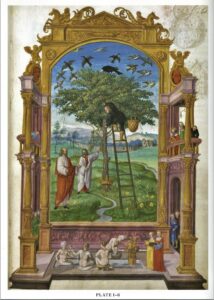

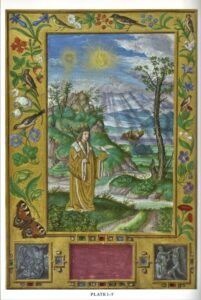

The Splendor Solis has long occupied a unique place in the Western alchemical canon, celebrated not only for the ambition of its text but above all for the sumptuous series of twenty-two emblematic illuminations that accompany it. With the publication of Splendor Solis: The World’s Most Famous Alchemical Manuscript, Stephen Skinner has at last given modern readers a reliable, richly illustrated edition that unites rigorous scholarship with full-colour reproductions of the Harley MS 3469 held in the British Library. This volume, enhanced by contributions from Rafał T. Prinke, Georgiana Hedesan, and a new translation by Joscelyn Godwin, marks a watershed moment in the reception of this Renaissance masterpiece.

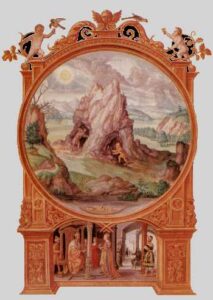

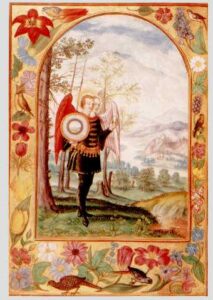

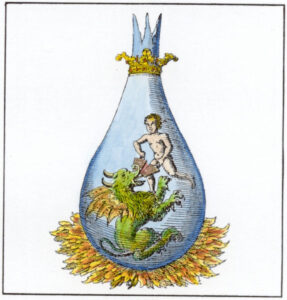

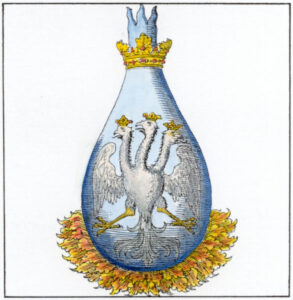

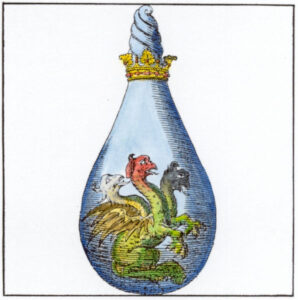

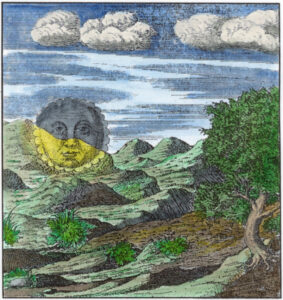

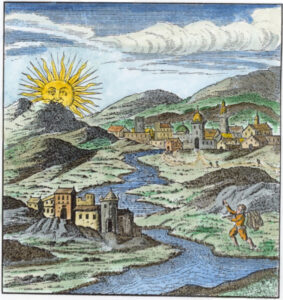

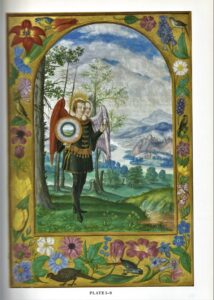

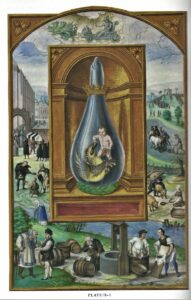

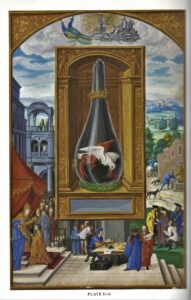

Skinner opens the book with an introduction that resists the temptation—so prevalent in the twentieth century—to read Splendor Solis through the lenses of Jungian psychology or Tarot symbolism. He insists instead that the manuscript should be approached in its original context: as a practical, laboratory-minded treatise concerned with the transmutation of matter. He carefully maps the emblematic images onto the sequence of colour stages recognized by early alchemists—black, white, yellow, red—and connects them to parallel processes of metallurgical transformation. This grounding in physical practice allows the manuscript to be seen not as a vague allegory of individuation, but as a technical and visionary guide to the Great Work.

Rafał T. Prinke provides what is perhaps the most important scholarly essay in the volume: a detailed reconstruction of the text’s authorship and transmission. He shows that the Splendor Solis is not an original revelation but a florilegium, a patchwork of earlier alchemical authorities such as Aurora Consurgens, Donum Dei, and Turba Philosophorum. Prinke also reviews the evidence surrounding Ulrich Poyssel, to whom several manuscript witnesses attribute the work, while dismantling the long-standing but spurious connection to Salomon Trismosin. His account of the manuscript and print traditions—from the unillustrated copies of the mid-sixteenth century to the 1599 Aureum Vellus edition and its later misattributions—anchors the book firmly in the historical record.

Georgiana Hedesan widens the frame by examining how Splendor Solis fits into the Paracelsian milieu of the sixteenth century, where the figure of the adept was being reimagined as both natural philosopher and inspired seer. Her essay situates the manuscript in a culture where alchemical knowledge was being used to stake intellectual authority as much as to promise transmutation. She also provides a glossary of the philosophers and works referenced in the text, a practical tool that underscores the work’s character as a compilation.

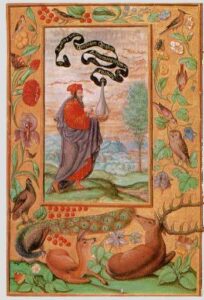

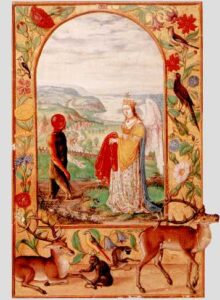

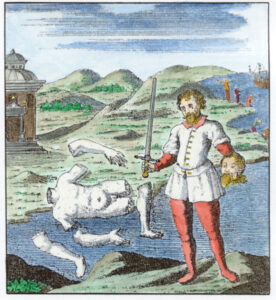

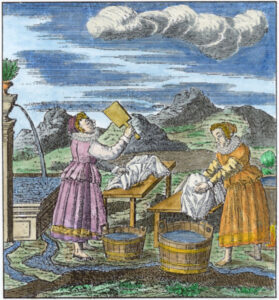

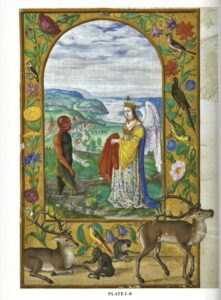

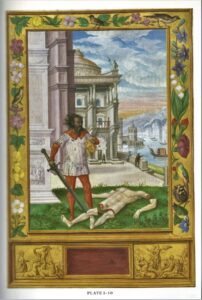

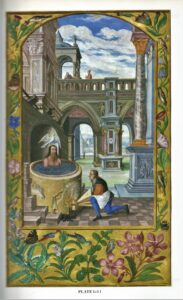

Joscelyn Godwin’s translation of Harley MS 3469 is the most accessible yet faithful rendering of the text into English. Where earlier translations either interpolated esoteric systems foreign to the manuscript or stripped away its strangeness, Godwin allows the voice of the Renaissance compiler to be heard. His translation of the seven parables—ranging from the King who drowns in the river to the Moor being washed by an angel—preserves the balance of mystery and instruction that defines the emblematic art.

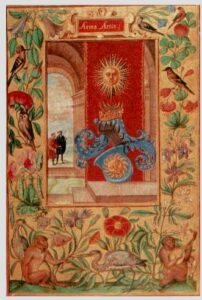

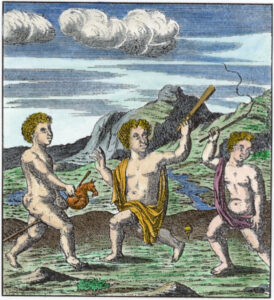

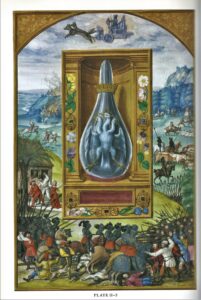

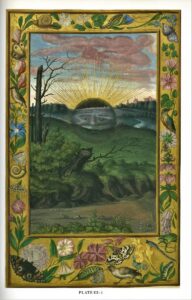

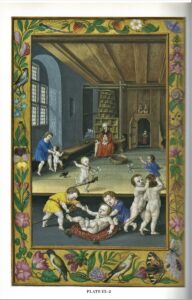

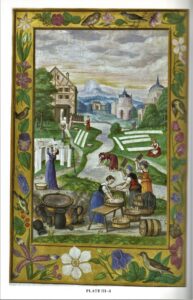

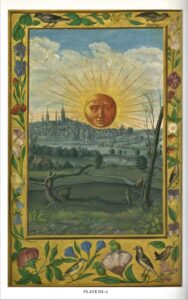

The heart of Splendor Solis remains its twenty-two plates, and the present volume does them justice. For the first time, general readers and scholars alike can appreciate the full richness of the illuminations: the planetary “children,” the peacock in its flask, the winged hermaphrodite, and the final rising of the red sun. Unlike the crude woodcuts of the Aureum Vellus or the black-and-white reproductions of the early twentieth century, these images restore the luminous, jewel-like splendour of the original.

Taken together, the essays and translation reposition Splendor Solis as both the culmination of the medieval alchemical florilegia and the prototype of the Renaissance emblem-book tradition that would soon flower in works like Michael Maier’s Atalanta Fugiens. The edition makes clear that while its textual substance is largely derivative, its imaginative synthesis and artistic execution are unparalleled. It is this union of careful compilation, inventive emblem, and radiant artistry that has secured the manuscript’s reputation as the crown jewel of Western alchemy.

This book succeeds precisely because it treats Splendor Solis on its own terms. Skinner reminds us that the adepts were not proto-psychologists but experimenters who believed they were perfecting nature’s processes. Prinke demonstrates the genealogy of its sources and the fabrication of its mythical authorship. Hedesan places it in its intellectual milieu, while Godwin restores its voice. The result is both a scholarly triumph and a feast for the imagination. For anyone serious about the study of alchemy, this edition is not simply useful; it is indispensable.

Hold this gorgeous book in your hands.

Research Index Entry: Splendor Solis

Full Title: Splendor Solis: The World’s Most Famous Alchemical Manuscript (Harley MS 3469, British Library; modern edition by Stephen Skinner, 2019)

Splendor Solis. The World’s Mos…

Attributed Authors:

-

Commonly ascribed to Salomon Trismosin (via 1612 La Toyson d’or French translation, erroneous attribution).

-

Modern research (Rafał T. Prinke): strong evidence links text to Ulrich Poyssel (Canonicus), a mid-16th century figure connected with Spiegel der Alchemie.

-

Earlier textual strata draw heavily on Aurora Consurgens (c. 1420), Donum Dei, Rosarium Philosophorum, Buch der Heiligen Dreifaltigkeit, and Visions of Zosimos.

Dating & Manuscript Tradition:

-

Earliest manuscripts: mid-16th century. Illuminated codices dated 1531–1577 (Berlin, Nuremberg, Paris, London, etc.).

-

Unillustrated manuscripts: Leiden Q6 (pre-1550), Copenhagen (before 1550), Wolfenbüttel (1578), Munich (c. 1578), Prague (before 1590), Leiden Q17 (1595), Kassel 11 (c. 1600).

-

Illuminated cycle: Seven deluxe parchment copies (Berlin, Nuremberg, Paris, London, Kassel, Philadelphia, etc.), all stemming from one archetype.

Printed Tradition:

-

First printed: Aureum Vellus, Vol. 3 (Rorschach, 1599), with crude woodcuts, no attribution to Trismosin.

-

Pirated reprint: Leipzig, 1600 (Henning Gross).

-

Expanded circulation: Hamburg, 1708/1718 (Eröffnete Geheimnisse des Steins der Weisen).

-

Misattribution: 1612 Paris La Toyson d’or (Charles Sevestre, with “L. I.” translator), which linked text to Trismosin.

Content & Structure:

-

Seven treatises; central treatise includes seven parables, closely paralleling Aurora Consurgens.

-

22 emblematic plates: planetary miniatures, allegorical parables (e.g. Drowning King, Moor & Angel, Hermaphrodite with Egg, Peacock in flask), culminating in the Red Sun.

-

Textual character: a florilegium—a patchwork of earlier alchemical dicta, especially from Aurora Consurgens, Turba Philosophorum, Tabula Chemica of Senior Zadith.

Themes & Frameworks:

-

Physical alchemy focus: sequences of colour transformations (black, white, yellow, red), metallurgical allegories.

-

Excludes: overt Christian allegories (as in Buch der Heiligen Dreifaltigkeit), and explicit sexual symbolism (as in Donum Dei).

-

Symbolic uniqueness: planetary “children” scenes; merging of classical motifs (Virgil’s Golden Bough, Ovid’s Metamorphoses) with alchemical parables.

Key Scholarship (modern edition):

-

Stephen Skinner: rejects Jungian/Tarot overlays; insists on physical laboratory context.

-

Rafał T. Prinke: manuscript genealogy, authorship (Ulrich Poyssel), print history.

-

Georgiana Hedesan: Paracelsian context; glossary of referenced philosophers.

-

Joscelyn Godwin: definitive English translation of Harley MS 3469.

Significance:

-

Crown jewel of alchemical art: unrivalled illuminations, complex synthesis of medieval and Renaissance alchemical traditions.

-

Bridges late medieval florilegia with Renaissance emblem-books, setting stage for Maier’s Atalanta Fugiens (1617).

-

Enduring fascination: from Rudolf II’s court to Golden Dawn and Jungian reappropriation.